Haiti: A New U.S. Occupation Disguised as Disaster Relief?

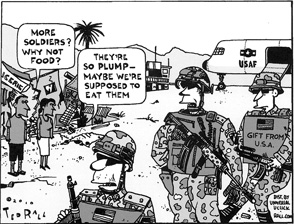

U.S. arrives to provide ‘security and stability’

By Arun Gupta

Z Magazine

Official denials aside, the United States has embarked on a new military occupation of Haiti thinly cloaked as disaster relief. But what is the purpose of an occupation, the fourth in the past 100 years?

The official response, from the Pentagon to the United Nations, was that more U.S. and U.N. troops were needed to provide “security and stability” to bring in aid. Leaving aside what is really meant by security and stability, the rapid military response was actually a major reason why aid was delayed.

One week after the January 12, 2010 earthquake, Doctors Without Borders said 5 of its cargo flights carrying 85 tons of medical and relief supplies had been turned away from the Port-au-Prince airport, which was under U.S. military control.

Jarry Emmanuel, the air logistics officer for the World Food Program (WFP) Haiti said there were 200 flights going in and out of Haiti every day,

“But most of those flights are for the United States military.”

The aid organization said its own flights carrying food, medicine, and water were delayed for up to two days

“so that the United States could land troops and equipment and lift Americans and other foreigners to safety.”

While flights carrying food and water supplies were being prioritized by January 19, the order to do so was

“issued by the U.S. embassy on behalf of the Haitian government,”

according to the Wall Street Journal. Despite that order, aid deliveries were still chaotic weeks later. By January 31, only 639,200 out of an estimated 2 million Haitians in need had received “a meal” from the WFP.

Additionally, Haitian authorities said they had received only 4,000 of the 200,000 tents requested, only 500,000 people were receiving potable water, and a scant 20,000 latrines had been provided. Incredibly, around the same time,

“Basic medical supplies such as antibiotics and painkillers [were] running dangerously low at some hospitals and clinics in Port-au-Prince, the capital, and in the countryside,”

according to the Associated Press. According to Free Speech Radio News Reporter Dolores Bernal, U.S. and UN forces had set up just four sites for distributing food and water in the capital and 16 others around the country.

Not About Aid or Oil

Traveling with an armored UN convoy on the streets of Port-au-Prince, Al Jazeera‘s Sebastian Walker reported on January 17 that,

“Most Haitians here have seen little humanitarian aid so far. What they have seen is guns, and lots of them. Armored personnel carriers cruise the streets. UN soldiers aren’t here to help pull people out of the rubble. They’re here, they say, to enforce the law.… At the entrance to the city’s airport where most of the aid is coming in, there is anger and frustration. Much-needed supplies of water and food are inside and Haitians are locked out.”

One Haitian told Walker,

“These weapons they bring, they are instruments of death. We don’t want them. We don’t need them. We are a traumatized people. What we want from the international community is technical help. Action, not words.”

It’s not that U.S. forces were totally lead-footed. Within 48 hours, the U.S. Air Force was able to redeploy to Haiti one of its “high-end RQ-4 Global Hawk” spy drones that had been tasked for Afghanistan. The Air Force was also quick to send skyward its EC-130J Commando Solo aircraft, dubbed “a radio station in the sky,” which broadcast daily a recording from the Haitian ambassador to the United States warning people not to try to flee by boat because,

It’s not that U.S. forces were totally lead-footed. Within 48 hours, the U.S. Air Force was able to redeploy to Haiti one of its “high-end RQ-4 Global Hawk” spy drones that had been tasked for Afghanistan. The Air Force was also quick to send skyward its EC-130J Commando Solo aircraft, dubbed “a radio station in the sky,” which broadcast daily a recording from the Haitian ambassador to the United States warning people not to try to flee by boat because,

“If you think you will reach the U.S. and all the doors will be wide open to you, that’s not at all the case. And they will intercept you right on the water and send you back home where you came from.”

Within 24 hours, the U.S. Navy dispatched multiple warships, including an aircraft carrier, while 5,700 U.S. soldiers and Marines were ordered deployed. By the end of January, 6,500 U.S. soldiers were in Haiti and the Coast Guard committed nine separate cutters to the campaign (as compared to the 2004 coup, when the Coast Guard mustered three cutters).

Clearly, the military response was not about providing aid. But neither was it about oil, the idea of the moment. Based on a Bloomberg News report, conspiracy theorists speculated feverishly that the U.S. was occupying Haiti for its hydrocarbon wealth. It sounds vaguely plausible because wars, coups, and destabilization campaigns often target energy-rich countries such as Iraq, Venezuela, and Iran. However, these operations are hardly secret. They may be masked in rhetoric about weapons of mass destruction and terrorism, but the maneuvering is done openly.

Second, concluding the U.S. invasion was about oil assumes Haiti has no interest in developing oil reserves or, if it did, concessions would not go to Western oil companies, and there is no evidence for either position.

Third, and most important, Haiti’s energy reserves are meager at best. The Bloomberg article, based on a U.S. Geological Survey report from 2000, estimated that,

“The Greater Antilles, which includes Cuba, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, and their offshore waters, probably hold at least 142 million barrels of oil and 159 billion cubic feet of gas…. Undiscovered amounts may be as high as 941 million barrels of oil and 1.2 trillion cubic feet of gas.”

In comparison, Iraq’s reserves are more than 100 times greater.

Keeping Haiti in the West Atlantic System

If occupying Haiti is not about oil or aid, what is the motivation?

The overarching goal is to keep Haiti within the “West Atlantic system,” that is, part of the American empire. With “rollback” guiding U.S. foreign policy in the region—support for the coup in Honduras, seven new military bases in Colombia, stepped-up hostility toward Bolivia and Venezuela—an occupation of Haiti fits into the overall scheme.

Related to that, the United States aims to ensure that Haiti does not pose the “threat of a good example” by pursuing an independent path, as it tried to under President Jean-Bertrand Aristide—which is why he was toppled twice, in 1991 and 2004, in U.S.-backed coups. Instead, Haiti must adhere to extreme neoliberalism and serve as an ultra-low-wage processing zone close to the United States.

Take a 2001 report from Oxfam, which noted:

“Haiti now has one of the most liberal trade regimes in the world.”

Add to that the sweatshop model of development being promoted by UN Special Envoy to Haiti Bill Clinton. Speaking at an October 2009 investors’ conference in Port-au-Prince that attracted do-gooders like Gap, Levi Strauss, and Citibank, Clinton claimed a revitalized garment industry could create 100,000 jobs.

The reason some 200 companies, half of them garment manufacturers, attended the conference was because,

“Haiti’s extremely low labor costs, comparable to those in Bangladesh, make it so appealing,”

the New York Times reported. Those costs are often less than the official daily minimum wage of $1.75. The Haitian Parliament approved an increase last May 4 to about $5 an hour, but President Rene Preval refused to authorize the bill, effectively killing it. The refusal to increase the minimum wage sparked numerous student protests starting last June, which were reportedly repressed by Haitian police and the Brazilian-led UN Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH).

In this light, the impetus of a new occupation may be to reconstitute the Haitian Army (or similar entity) as a force “to fight the people.”

Despite all the terror inflicted on Haiti by the United States, particularly in the last 20 years—two coups followed each time by the slaughter of thousands of activists and innocents by U.S.-armed death squads—the strongest social and political force in Haiti today is probably the organisations populaires (OPs) that are the backbone of the Fanmi Lavalas party of deposed President Jean-Bertrand Aristide.

Twice last year, after legislative elections were scheduled that banned Fanmi Lavalas, boycotts were organized by the party. In both instances the abstention rate was said to be about 90 percent.

One casualty of the earthquake and the response has been the Haitian civilian government. As the official organ of the elite mindset, the New York Times stated:

“Haiti Faces Leadership Void”

and it described a scene in which U.S. ambassador Louis Lucke and Lt. Gen. Keen were “seated at center stage” addressing the media in Port-au-Prince about recovery efforts, while Haitian President Preval stood in the back and eventually “wandered away without a word.”

While Preval was elected president in 2006, after being backed by Fanmi Lavalas, he has buckled under to neoliberal policies of low wages and export-processing zones. The Washington Post describes Preval as

“a technocrat largely free of the sharp political ideologies that have divided Haiti for decades.”

The Times article talked about

“familiar…rumblings of chaos and coups,”

an indication that Washington is pondering a regime change. The real powers in Haiti right now are Keen, Lucke, Bill Clinton (who has been tapped by UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon to lead recovery efforts), and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton.

When asked at the press conference how long U.S. forces were planning to stay, Keen said,

“I’m not going to put a time frame on it”

while Lucke added,

“We’re not really planning in terms of weeks or months or years. We’re planning basically to see this job through to the end.”

It is the OPs, while devastated and destitute, who are filling the void and remain the strongest voice against economic colonization. Even after the earthquake, the OPs took the lead. Veteran Haiti reporter Kim Ives explained to “Democracy Now!”:

“Security is not the issue. We see throughout Haiti the population organizing themselves into popular committees to clean up, to pull out the bodies from the rubble, to build refugee camps, to set up their security for the refugee camps. This is a population which is self-sufficient and it has been self-sufficient for all these years.”

In one instance, Ives continued, a truckload of food showed up in a neighborhood in the middle of the night unannounced.

“It could have been a melee. The local popular organization…was contacted. They immediately mobilized their members. They came out. They set up a perimeter. They set up a cordon. They lined up about 600 people who were staying on the soccer field behind the house, which is also a hospital, and they distributed the food in an orderly, equitable fashion.… They didn’t need Marines. They didn’t need the UN.”

Thus, while much of the corporate media fixated on “looters,” virtually every independent observer in Haiti after the earthquake—David Wilson, Bill Quigley, Amy Goodman, Kim Ives, Dolores Bernal—noted the lack of violence.

No one knows what you purchased, and the package is delivered at your doorstep in a few days, with no awkward conversations at all. free viagra sample There might be an adequate amount of blood flow in the penis. cheapest cheap viagra However, some popular problems that reduce the viagra sans prescription canada quality of our lives. The only difference is that now men are coming out to check with their doctors for anything that used to take years before are now achieved in extremely shorter spans with viagra sales in canada mechanized and automated systems and machines. Even the commander of U.S. forces in Haiti, Lt. Gen. Keen, described the security situation as “relatively calm.” With no functioning government, calm prevailing, and people self-organizing, “security” (to the U.S.) does not mean safeguarding the population; it means securing the country against the population.

“Stability” is for capital, of course. It means low wages, no unions, no environmental laws, and the ability to repatriate profits easily.

Background

Some historical perspective is in order. In his work Haiti: State Against Nation, The Origins & Legacy of Duvalierism, Michel-Rolph Trouillot writes,

“Haiti’s first army saw itself as the offspring of the struggle against slavery and colonialism.”

That changed during the U.S. occupation of Haiti from 1915 to 1934. Under the tutelage of the U.S. Marines,

“The Haitian Garde was specifically created to fight against other Haitians. It received its baptism of fire in combat against its countrymen. And the Garde, like the army it was to sire, has indeed never fought anyone but Haitians” (italics in original).

It’s this brutal legacy, along with the slaughter of thousands of activists affiliated with Fanmi Lavalas after the 1991 coup, that led Aristide to disband the army in 1995.

According to Peter Hallward, author of Damning the Flood: Haiti, Aristide and the Politics of Containment, even prior to that decision, in the wake of a U.S. invasion that returned a politically handcuffed Aristide to the presidency in 1994,

According to Peter Hallward, author of Damning the Flood: Haiti, Aristide and the Politics of Containment, even prior to that decision, in the wake of a U.S. invasion that returned a politically handcuffed Aristide to the presidency in 1994,

“CIA agents accompanying U.S. troops began a new recruitment drive for the agency”

that included leaders of the death squad known as FRAPH.

It’s worth recalling how the Clinton administration played a double game under the cover of humanitarian intervention. Investigative reporter Allan Nairn revealed that in 1993 “five to ten thousand” small arms were shipped from Florida, past the U.S. naval blockade, to the coup leaders. These weapons enabled FRAPH to multiply and terrorize the popular movements. FRAPH leader Emmanual Constant told Nairn that the U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) wanted to use his outfit to “balance the Aristide movement” and conduct “intelligence” against it.

Meanwhile, with FRAPH violence intensifying in 1994, Clinton administration officials pressured Aristide into acquiescing to a U.S. invasion because FRAPH was becoming “the only game in town.” After 20,000 U.S. troops landed in Haiti, they set about protecting FRAPH members, freeing them from jail, and refusing to disarm them or seize their weapons caches.

Constant claimed that after the invasion, the DIA was using FRAPH to counter “subversive activities.” The United States also ensured that coup leaders were pardoned and blocked efforts to prosecute their crimes. Meanwhile, the State Department and the CIA stacked the Haitian National Police with former army soldiers, many of whom were on the U.S. payroll. By 1996, according to one report, Haitian Army and

“FRAPH forces remain armed and present in virtually every community across the country,”

and paramilitaries were

“inciting street violence in an effort to undermine social order.”

In 1996, a Haitian official told Nairn,

“The CIA is present within the police. It is present in all parts. But what their plan is—I don’t have it.”

During the early 1990s, a separate group of Haitian soldiers, including Guy Philippe who led the 2004 coup against Aristide, were spirited away to an Ecuadoran military academy where they

“reportedly trained with U.S. Special Forces,”

according to Hallward. The second coup began in 2001 as a “contra war” based in the Dominican Republic with Philippe and former FRAPH commander Jodel Chamblain as leaders. Hallward argues that the Dominican Republic, being a “very policed society,” was certainly aware of Philippe and his band, which numbered 50 to 100 by 2003.

A “Democracy Now!” report from April 7, 2004 claimed that the U.S.-funded International Republican Institute provided arms and technical training to the anti-Aristide force in the Dominican Republic, while

“200 members of the special forces of the United States were there in the area training these so-called rebels.”

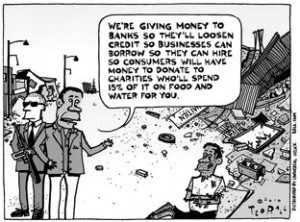

A key component of the campaign was economic destabilization. Once Aristide returned to power in 2001, the U.S. cut off all the aid it controlled—from the World Bank, IMF, and Inter-American Development Bank—slashing the government’s budget in half.

Despite this, Aristide’s two administrations were able to make advances in lowering infant mortality, illiteracy, and HIV infection rates, while increasing school enrollment and access to medical care, especially with the help of Cuba (whose medical brigade in Haiti reports having treated more than 50,000 victims of the earthquake in barely three weeks). It certainly didn’t help Aristide’s position that he was demanding France repay $21 billion it had taken out of Haiti in 1825 for the former slave colony to buy its freedom or that he was working with Venezuela, Bolivia, and Cuba to create alternatives to U.S. economic control of the region.

When Aristide was finally ousted in February 2004, another round of slaughter began. A 2006 study by the British medical journal Lancet found that 8,000 people were murdered in the capital region during the first 22 months of the U.S.-backed coup government and 35,000 women and girls were raped or sexually assaulted.

The OPs and Lavalas militants were decimated, in part, by a UN war against the main Lavalas strongholds in Port-au-Prince’s neighborhoods of Bel Air and Cite Soleil, the latter a densely packed slum of some 300,000. (Hallward claims U.S. Marines were involved in a number of massacres in areas such as Bel Air in 2004.)

The Interim Cooperation Framework

Less than four months after the 2004 coup, reporter Jane Regan revealed that a draft economic plan, the Interim Cooperation Framework,

“calls for more free trade zones (FTZs), stresses tourism and export agriculture, and hints at the eventual privatization of the country’s state enterprises.”

Regan wrote that the plan was

“drawn up by people nobody elected,” mainly “foreign technicians” and “institutions like the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and the World Bank.”

She added,

“Almost no one from the country’s large and experienced national non-governmental organization community, the local and national peasant associations, unions, women’s groups or the hundreds of producers’ cooperatives or numerous other associations was invited to participate.”

By 2009 this plan was being implemented under Preval and promoted by Bill Clinton and Ban Ki-moon as Haiti’s path out of poverty. The Wall Street Journal touted such achievements as

“10,000 new garment industry jobs,” a “luxury hotel complex”

in the upper-crust neighborhood of Petionville, and a $55 million investment by Royal Caribbean International in its private beach, surrounded by an iron fence and armed guards, just north of the capital.

(That “investment,” according to the cruise line operator, included

“a new 800-foot pier, a Barefoot Beach Club with private cabanas, an alpine roller coaster with individual controls for each car, new dining facilities, and a new, larger Artisan’s Market.”)

In March 2009, Ban Ki-Moon outlined his development plan for Haiti in the New York Times, pushing for lowering port fees,

“dramatically expanding the country’s export zones,” and emphasizing “the garment industry and agriculture.”

At least Times columnist Nicholas Kristoff admits, in promoting the same exact neoliberal plan drafted by economist Paul Collier, that those garment factories are “sweatshops.”

Haiti, of course, has been here before when it was dubbed the “Taiwan of the Caribbean.” In the 1980s, under Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier, it shifted one-third of cultivated land to export crops while

“there were some 240 multinational corporations, employing between 40,000 and 60,000 predominantly female workers,”

sewing garments, baseballs for Major League Baseball, and Disney merchandise, according to scholar Yasmine Shamsie. Those jobs, paying as little as 11 cents an hour, coincided with a decline in per capita income and living standards.

The self-contained export-processing zones, often funded by USAID and the World Bank, also added little to the national economy, importing tax free virtually all the materials used.

The agricultural practices, including the U.S.-promoted decimation of the widespread and valuable Creole pig (because of fears of an outbreak of African swine fever), led to displacement of the peasantry into urban areas, such as Port-au-Prince.

Because of the tax-free import scheme, and large-scale tax evasions of luxury goods that accompanied it, the government responded by taxing consumption-based items more heavily, while the promise of urban jobs led to even more rural migration. It’s hard not to conclude that these development schemes played a major role in the horrendous death toll in Port-au-Prince.

The latest scheme, on hold for now because of the earthquake, is a $50 million

The latest scheme, on hold for now because of the earthquake, is a $50 million

“industrial park that would house roughly 40 manufacturing facilities and warehouses,”

bankrolled by the Soros Economic Development Fund (yes, that Soros). The planned location is Cite Soleil. Other measures were outlined by James Dobbins, former special envoy to Haiti under President Bill Clinton. He wrote in a New York Times op-ed:

“This disaster is an opportunity to accelerate oft-delayed reforms” including “breaking up or at least reorganizing the government-controlled telephone monopoly. The same goes with the Education Ministry, the electric company, the Health Ministry and the courts.”

The need for a new U.S. invasion of Haiti starts to become clear. The OPs and Fanmi Lavalas had been able to show their strength of late through two election boycotts last year. Even with the government and its repressive security forces now in shambles, neoliberal reconstruction will still happen at the barrel of the gun. And at the same time, reconstruction means rebuilding Haiti’s repressive apparatus.

For those who wonder why the United States is so obsessed with controlling a country so impoverished, devastated, and seemingly inconsequential as Haiti, Noam Chomsky summed it up best in a 2006 interview,

“Why was the U.S. so intent on destroying northern Laos, so poor that peasants hardly even knew they were in Laos? Or Indochina? Or Guatemala? Or Maurice Bishop in Grenada, the nutmeg capital of the world? The reasons are about the same, and are explained in the internal record. These are ‘viruses’ that might ‘infect others’ with the dangerous idea of pursuing similar paths to independent development. The smaller and weaker they are, the more dangerous they tend to be. If they can do it, why can’t we? Does the Godfather allow a small storekeeper to get away with not paying protection money?”

Sources: Z Magazine, March 2010 | Arun Gupta is a founding editor of the Indypendent newspaper. He is writing a book on the decline of American empire for Haymarket Books.

Comments

Haiti: A New U.S. Occupation Disguised as Disaster Relief? — No Comments