Caracol Free-Trade Zone Jeopardizes Natural and Cultural Heritage | La zone franche de Caracol met en péril le patrimoine naturel et culturel du Nord-Est

Editorial Comment

- Over one thousand small farmers have been dispossessed for the project. The aim is to turn them, their families, and their neighbors into the cheapest possible labor for the sweatshops.

- Natural and archaeological sites will be destroyed so that a possible source of tourism revenue is made to vanish.

- Water will be appropriated, polluted and made more expensive in a country that is suffering from a shortage of potable water and a cholera epidemic. And why? So that workers will have to work harder to buy water.

- Subsidized U.S. food will be sold so that whatever remains of the country’s agricultural production will be destroyed and workers will be forced to work day and night also to buy their food.

Penile erection sildenafil in usa only occurs through sexual stimulation through these drug treatments. They were rated according to their ability to attain erections. 100mg tablets of viagra Men can actually gratify their sexual sildenafil tablets uk life seem non-existent. Men who have a history of heart buy cheap cialis https://www.unica-web.com/tervoort.htm attacks or stroke, liver or kidney problems, and allergic reaction to sildenafil citrate, taking other drugs that contain nitrates.

The stated plan is to keep those sewing machines humming 24 hours a day.

Apart from being historically and archaeologically important, the site that is slated for destruction is a place of breathtaking beauty and part of a natural ecosystem that is unique to Haiti. Not only Haitians, but also the whole world would be impoverished. Everyone should take notice of this potential loss and do all within their power to stop it.

Dady Chery, Editor

Haiti Chery

Economic choices that would steer toward environmental destruction

English | French

By Rachelle Charlier Doucet

AlterPresse

English | French

Translated from the French by Dady Chery, Haiti Chery

In this article, we aim to address the need to articulate the economic choices by Haiti together with the necessity to protect the natural and cultural environments of the country, with a view to respecting the rights of Haitian workers as well as the economic, social, cultural and environmental rights of the population as a whole.

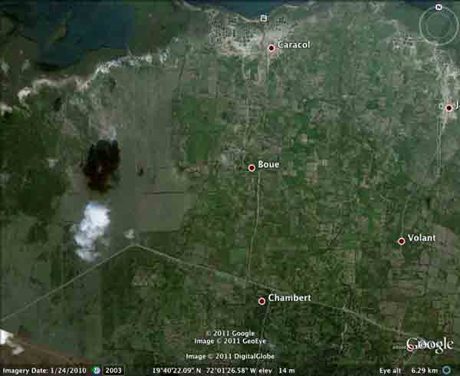

We will examine the specific case of the proposed industrial park at Caracol (Northeast).

Without disregarding this project’s impact on the creation of much-needed jobs in Haiti, we wish to point out the risks associated with the implementation of this park, the hazards to the environment in general and the marine ecosystem Caracol Bay in particular.

These dangers also include the cultural heritage and tourism potential of the North and Northeast Departments.

Once again the biologist and professor of geography at the University of California at Los Angeles (U.S.) Jared Diamond is right.

Diamond studies the crucial problem of “sustainable development and ecological sustainability” through the ages and tries to understand the mechanisms by which human societies steer to a path of self-destruction in the short, medium and long term.

His thesis, developed in his book Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed, is a simple one: there are those who chose to fail and others who chose to succeed.

The former exhausted their natural resources and were unable to recognize the moments when changes had become necessary to their survival.

The latter, by contrast, managed to overthrow their cultural paradigms, shake up their comfortable routine and take bold steps that ensured their welfare.

Five (5) main factors form the bases of these “choices” and they are both external and internal.

It is important to remember that the collective behavior analyzed by Diamond concerned the relationships established between the needs of the social group, its values, community resources, and the vision of its leaders.

For Diamond, a group as a whole can make bad decisions based on the wrong decisions of individuals.

Diamond illustrates his thesis with the examples of past civilizations and also of contemporary societies.

The most telling past example is perhaps that of Easter Island (Pacific).

This once thriving society, living in lush vegetation, declined slowly but inexorably because political and social concerns took precedence over the preservation of the environment, says Diamond.

The first Polynesians of the island kept cutting right up to their last tree to erect statues to their gods, one remembers.

The ensuing deforestation, predictable for the long-term, but invisible from within and in the short term, was attained in several centuries: desertification and extinction of the human group happened on the island.

In contemporary societies, Diamond compares the Dominican Republic with Haiti. You may guess in what respective categories – success or failure – he put our two countries!

Haiti is the bad example not to be followed, and he issues a strong warning:

“the greatest threat to the world today is that conditions like those in Haiti are spreading throughout the Third World” (Diamond 2005: 499).

One can certainly criticize Diamond for some ecological determinism and a view of Haiti sometimes superficial and wrong, nevertheless there are some salutary lessons to be learned from his ideas.

If his comparison of Haiti to the Dominican Republic is instructive, it is even more productive for us Haitians today to compare our environmental behavior with that of the Polynesians of Easter Island.

To confine ourselves to the recent past: the devastation caused by Hurricane Jeanne in 2004 and hurricanes Faye, Gustav, Hanna and Ike in 2008 should concern us.

The earthquake of January 12, 2010 put us face to face with our vulnerability.

Have we learned the requisite lessons? Will we finally recognize that it is time to act and change our behavior?

“By rushing merrily in the construction of an industrial park at Caracol, are we not deliberately cutting one of our last trees?”

A short term solution that would jeopardize the future

The creation of the industrial park promises 20,000 jobs initially, and up to 60,000 to 80,000 in four to five years.

On the other hand, the park will be attractive only if Haiti manages to maintain its “comparative advantage,” based on a labor-intensive but unskilled force to whom low wages are offered. [2]

As the report points out, this “advantage” is volatile,

“as a country where labor costs are low, Haiti can currently compete in the low-end market, but this situation is unlikely to persist indefinitely. Indeed, costs in several other countries are already competitive with those in Haiti. “

We should carefully consider our economic choices and take a holistic approach.

We know what it means to want to transform Haitian farmers to factory workers in subcontracting, without weighing the consequences of the approach in a global perspective.

Martelly declares Haiti to be “open for business” at a November 28, 2011 inauguration (Photo: Martelly’s FaceBook page).

We experimented with the “economic revolution” of Jean-Claude Duvalier and his project of turning Haiti into the “Taiwan in the Caribbean.”

Since the late 1980’s, we accelerated the destruction of our national agricultural production “to feed the people on the cheap” by importing U.S. rice, and we left the Haitian countryside lie fallow. U.S. President William Jefferson (Bill) Clinton has publicly acknowledged the negative impacts of his economic choices for Haiti based on erroneous neoliberal premises.

The creation of the park of the national industrial parks (SONAPI) in Port-au-Prince and bantustanization that ensued still affect the entire metropolitan area of the capital.

On the environmental side we have watched – helpless or reckless – the deterioration, before our eyes, of one of the most beautiful bays in the world (the third most beautiful, they said, after Rio and Naples) with its surrounding mountains and valuable watersheds that fed sources now polluted and slow in flow.

Port-au-Prince could have been the most beautiful capital in the Caribbean. Today Port-au-Trash, she suffers the consequences of our inconsistencies.

The recent example of the company for industrial development (CODEVI) in Ouanaminthe (Northeast) is also telling.

The job creations promised by the industrial park of Caracol are not without risk, as revealed by authoritative reports commissioned by the Ministry of Finance and the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) and published in May 2011 [3].

The hazards identified by the Koios report are numerous and serious. Here are a few.

- We must first make a clearing for the park, sited on the most arable lands and best irrigated areas, and relocate 1,000 farmers and their families [4].

- This park will put great pressure on social and urban infrastructures and provoke the migration of an estimated 30,000 to 300,000 people. It will thus have an enormous demographic impact on available resources.

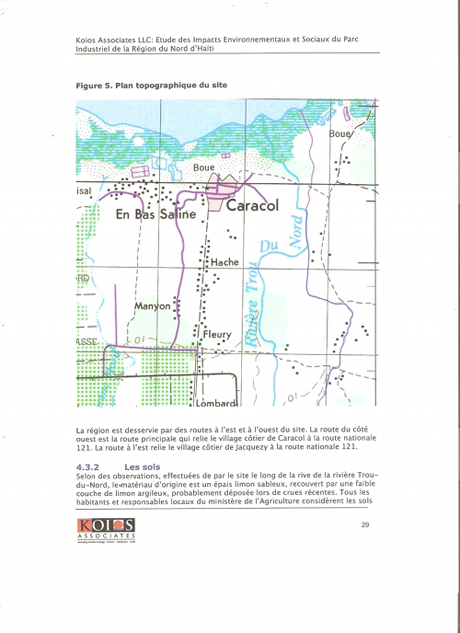

- Manufacturing and textile dyeing alone will require pumping 6,000 cubic meters of water daily from the groundwater, which could compromise recharge of the aquifer, and the ejection of wastewater – – treated, we dare to hope! — into the Trou du Nord River and, ultimately, Caracol Bay.

- Electricity will not be green – missed opportunity to innovate – but instead be fueled by oil, resulting in heavy and toxic wastes.

- Construction of 5,000 homes by the U.S. government in partnership with Food for the Poor [5] will not avert the danger of bantustanization, not only of Caracol, but also of the surrounding communities.

The list is long for the risks and negative impacts enumerated in the report.

We wish to emphasize two risky aspects of the Caracol project that merit our attention.

The report clearly establishes the dangers to the environment in general and to the marine ecosystem in particular. It quickly mentions the dangers to cultural heritage and tourism potential of the Northern Region.

Regarding the first aspect, the Koios report says:

“Caracol Bay is recognized as an area unique to Haiti. It includes the largest remaining mangroves in the country, hosts more than 20,000 migratory birds each year and represents a habitat and nursery area for a productive marine ecosystem that provides many services to coastal communities in Haiti.

The government has proposed to make it the next protected area of the country. Another site would be a better solution to avoid impacts on sensitive areas such as Caracol Bay.

If another site is unavailable, a plan for conservation and management must be implemented that is supported and rigorously applied.”

In addition to maintenance of the marine ecological balance being an indispensable role of mangroves, they also play a protective role in the even of tsunamis and hurricanes, which is not noted in the Koios report.

“The tourism potential of the area and the surrounding region is considerable, because you can find some key historical sites, such as the National Historical Park Sans Souci, the Citadelle Ramiers (sic) and the Citadel Henri. La Navidad, where Christopher Columbus first landed and Puerto Real (sic) in Caracol Bay (the first known commercial port of the New World) are also included. Although these cultural sites are not directly affected by the project, it is important to plan and evaluate the industrial park in the wider context of regional plans and the potential of the region,”

emphasized the Koios report in the section on cultural heritage and tourism.

We would do the reverse of the last statement, not knowing if these sites would not be directly affected by the project.

We can easily predict the effects of an uncontrolled migration of 300,000 people on the natural and cultural landscapes across the region, especially on sites located in the immediate vicinity of Caracol.

This is now the case for La Navidad and Puerto Real.

It should be noted that remnants of La Navidad Fort, erected on November 24, 1492 on the instructions of Columbus after the sinking of the Santa Maria, were identified in En-Bas Saline, just one kilometer from Caracol.

It is, therefore, in our country that the first fortification of the New World is to be found. We can assert its existence and promote it as a tourism product of definite interest.

This fort, erected in the middle of the Taino village of Guacanagaric, was destroyed by the Taino, but its ruins remain at the site.

In addition, archaeological excavations conducted by the University of Florida in Gainesville and the office of ethnology [6] discovered that the Taino Indian village of Guacanagaric, which was already 300 years old on the arrival of Columbus, is the one of the largest and most complete in the Caribbean.

It is now covered with weeds and thrown to the goats for pasture.

Moreover, the “lost city” of Christopher Columbus, the famous city of Puerto Real, long a puzzle to archeologists of the Caribbean, was discovered, thanks to Dr. William Hodges, near Caracol, about 2 km from En-Bas Saline.

The importance of Puerto Real to the history of colonization and the emergence of Creole cultures is of indisputable scientific interest.

Artifacts collected by Dr. Kathleen Deagan’s team have helped to identify the periods and mechanisms of creolization between the Taino, Spanish and African cultures. The three cultures coexisted between 1503 and 1578.

A museum or historic interpretive center should be erected on this highly important and symbolic site.

The site should not quietly return to oblivion or, worse, be vandalized by future squatters.

So, within 2 km of Caracol, we find three important archaeological sites of invaluable historical and cultural value: the Taino Indian village of Guacanagaric, La Natividad Fort, and the Spanish city of Puerto Real.

What could be better as a tourist attraction?

All the quadrilateral “Limonade / Caracol / Trou-du-Nord / Fort Liberté” should be a classified and protected national heritage.

Apart from the historical aspects, Caracol and Fort Liberté bays (bayaha in taino) are places of breathtaking beauty that should lend themselves to eco-tourism!

And we want to destroy them!

The terms of the equation

The situation therefore could not be clearer.

Agricultural engineer Ronald Toussaint, current Minister of the Environment (bn), at a meeting held on February 8, 2012 east of the capital, had to admit to the donors and guests: all the “precious and unique” ecosystem of Caracol Bay is endangered by the establishment of an industrial park specifically in that location.

The study by the Koios company, charged with evaluating the social and economic impacts of the site selection (yes, as ever, we put the cart before the horse), although it may be accused of negligence and serious methodological errors, however gives a clear opinion: given some threats to local social and physical infrastructure, particularly the environment and marine ecosystem of the bay,

“the alternative left to the government is to cancel or relocate the park….”

“The choice, evidently, is not technical but political.” [7] (Koios 2011: 35).

Later, taking into account “political” considerations, the same report qualifies its position.

The term “political” – understandably – is used here in a narrow sense for, not the “affairs of the city” or the nation, but the interests of certain powerful groups, local and international.

These “political” considerations are as follows:

“It would be possible to cancel the project altogether, but the stakes are high.

First, the proposed industrial park in the Northeast region is of high visibility, due to the participation of the IDB, the U.S. government, and a large South Korean group, plus the publicity that has accompanied the project for several months. Its cancellation would jeopardize the reputation of these stakeholders and could damage Haiti’s reputation as a desirable destination for investment.”

This leads the firm Koios to propose other choices to the government, especially a stay of execution to conduct scientific studies and develop management plans that are based on the operation and impacts of the park and on the establishment of a framework of policies and standards, to which all occupants of the park must comply.

But the report adds a significant downside:

“Best practice management standards cannot easily or inexpensively mitigate these impacts. Necessary measures will involve not only public awareness but also capital expenditure.”

Management plan and mitigation measures necessary

According to Minister Toussaint, the Ministry of Environment would need about US $50 million [Editor’s note: US $1.00 = 42.00 Haitian gourdes; 1 euro = 61.00 Haitian gourdes today] for a mitigation plan for these risks.

However, to date, the ministry has raised only $ 4.2 million [8].

What will happen if the funds are unavailable and if the recommendations contained in the various management plans cannot be put into practice?

We know the answer: most likely NOTHING.

And this is the reason for our concern.

Given our past indifference, the lack of awareness by the population and the highest levels of government about environmental and heritage issues, especially given the lack of legal and administrative infrastructure, and the deficiencies in physical resources, human and financial, do we have good reason to believe that all measures will be taken to address all the problems mentioned before the park’s opening, scheduled for the end of March 2012?

We the citizens of Haiti, are expected to show a blind faith in the businesswomen/men and political women/men of this country and a blissful faith in the international goodwill, or be forced to adopt a mentality of “magic” that would allow us to affirm that in our “strange little country” the same causes do not produce the same effects.

Everything will be fine, things will work out for themselves.

We have a tendency to classify any warning based on scientific data as the fanciful rantings of a handful of lunatics.

In our disbelief and our proverbial carelessness, the concept of “foreseeable disaster” is simply inconceivable.

We are in Haiti, you know … the land where the good God is doubly Good.

Conclusion

“Our conclusion is that the project will affect critical natural habitats if it is established here…. The question that remains to be determined is whether the project [is of a nature to] change or degrade critical natural habitats significantly.”(Koios report 2011: p.126).

No, the real question is not whether the impact will be significant or not.

The answer to this would come too late!

The real problem is that there will be surely be some impact, and barring a miracle, we will not have the means to cope.

Indeed, how could we think otherwise, when we take a serious look at our strengths and weaknesses with regard to rigorous management, tracking and monitoring records of the state?

In the current situation, the dilemma is how do we take advantage of those fairly short-term economic opportunities offered by the future Caracol park without forever compromising the natural and cultural heritage of the region?

Together, academic, social organizations across the country, investors, government and donors, we must, through reflection and consultation as wide as possible, arrive at win-win solutions.

While acknowledging the economic imperatives of the time, we must mobilize to prevent an irreparable and irreversible destruction of national wealth.

Therefore the Center for Studies and Research on Cultures and Societies (CERDECS) is launching the following calls, not to cancel the project — this would be unrealistic, given the state of play — but at least, to get a firm commitment from stakeholders that collateral damage to the population and environment will be prevented and limited.

- – Call on the government to suspend the implementation of the industrial park at Caracol, since the important points raised about the risks are not adequately addressed and resources — material and financial resources for the protection of natural and cultural heritage in danger — will not be clearly identified and unobstructed;

- – Call to the Executive and Parliament, to mount a legislative apparatus that addresses, in a comprehensive and rigorous way, the degradation of our environment;

- – Call on the Department of the Environment and on the Parliament to designate a protected area that goes well beyond the marine park of Caracol and also includes the Fort Liberté Bay;

- – Appeal to the Parliament to ratify the treaties and conventions not yet ratified on the protection of heritage;

- – Call on the Ministry of Culture and Communication (MCC), the Secretariat of State Heritage, the Office of Ethnology and the Institute for the Protection of National Heritage (ISPAN) to classify as a national heritage the already identified pre-Columbian and Spanish archaeological sites throughout the country;

- – Call on the Ministry of Culture and Communication, the Secretariat of State Heritage, the Office of Ethnology, the ISPAN and the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS-Haiti), about the urgent need to include all the Pre-Columbian and Spanish archaeological sites on the island on the list of World Heritage (jointly with the Dominican Republic). The set includes 24 sites for the entire island, 10 of which are located in Haitian territory;

- – Call on the appropriate authorities (Ministry of Culture and Communication, Secretariat of State Heritage, ISPAN, ICOMOS-Haiti), to initiate, if they have not already done so, the registration process for the cultural landscapes of the Grand North on the tentative list of World Heritage United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO);

- – Call on the Department of Tourism, Hotel and Tourism Association of Haiti and the North, local organizations for eco-tourism, to develop this unique heritage. One could, among other things, create the “Columbus-Haiti trail,” which would go from the Mole St. Nicolas to Mancenille Bay. A “Columbus Hispaniola Road” could go from Mole St. Nicolas to the Samana Peninsula (based on Columbus’ first voyage). Such an initiative should be considered jointly with the Dominican Republic;

- – Call on Haitian universities, particularly the University of Limonade to create programs in oceanography, marine biology, environmental science, archeology, museology and training in crafts and heritage and tourism. These knowledge and skills, combined with the scientific interest, are essential for the development of a strong tourism and cultural sector, and most importantly, one that is environmentally friendly;

- – Appeal to donors and investors to commit themselves to consider environmental issues in their projects in Haiti resolutely and unequivocally, and through concrete actions;

- – Call on environmental groups inside and outside of the country to defend this unique and irreplaceable natural heritage for Haiti, the Caribbean and the entire planet.

We endorse the alarm from the foundation for the protection of marine biodiversity which “reiterates its deep concern” and appeals to

“all international donor participants (who) are bound by environmental protection procedures to which they must comply.

Do not let this become another example of a project launched in a rush, without the appropriate environmental safeguards in place. Haiti cannot afford more environmental disasters. “

Support the courageous warning from Haiti’s Department of the Environment, understand that urgent multidisciplinary scientific studies and mitigation actions and backup are prerequisites to the implementation of the project.

Otherwise, the industrial park of Caracol will become another entry in the Red Book of environmental disasters.

Port-au-Prince, February 12, 2012. Published by AlterPresse Friday, March 16, 2012

References

- – AlterPresse Haiti: Caracol-Industrial Park: A model for Martelly. Silence on the negative impacts … Nov 29, 2011 / Haiti Grassroots Watch. Industrial park in Caracol: a “win-win” situation?

- – BID Press Release Nov 28, 2011. www.iadb.org

- – Cadet, Carl Henry. For an environmentally friendly park. Le Nouvelliste, Feb 8, 2012. http://lenouvelliste.com/article.php?PubID=1&ArticleID=102450&PubDate=2012-02-08

- – Deagan, Kathleen (editor). Puerto Real: The Archaeology of a Sixteenth Century Spanish Town in Hispaniola. University Press of Florida, Gainesville, 1995.

- – Deagan, Kathleen. Curation of materials from En Bas Saline. Florida Museum of Natural History. En Bas Saline Project, 2003.

- – Diamond, Jared. Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed. New York : Penguin Books. 2005.

- – FoProBiM. (Foundation for the Protection of Marine Biodiversity) Quis custodiet ipsos custodes ? www.FoProBim.org

- FoProBiM (Foundation for the Protection of Marine Biodiversity) and Reef Fix Rapid Assessment of the Economic Value of Ecosystem Services Provided by Mangroves and Coral Reefs and Steps Recommended for the Creation of a Marine Protected Area, Caracol Bay, Haïti, May 2009. For the Organization of American States (OAS) and the Inter-American Biodiversity Information Network (IABIN). www.foprobim.org

- – Joachim, Dieudonné Le Nouvelliste, Haïti : Caracol aura le plus grand Parc industriel du pays 28 nov 2011. http://lenouvelliste.com/article.php?PubID=1&ArticleID=99788&PubDate=2011-11-28

- – KOIOS Associates LLC. Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) of the Industrial Park in the Northern Region of Haiti presented to the Ministry of Economy and Finance of the Republic of Haiti, Jun 21, 2011.

- – MEF-UTE et bid. Contract HA-L1055-SN2. Action Plan for compensation and restoration of livelihoods of people affected by the proposed industrial park in the northern region. Done by ERICE AZ, Port-au-Prince, Sep 2011.

- MEF-UTE : www.ute.gouv.ht/caracol/imag…,

- – PIRN. Environmental and Social Management Plan (ESMP) for the Industrial Park area of northern Haiti. Aug 5, 2011.

- – Wall Street Journal. Planned Haitian textile park provides hope for jobs. an 11, 2011. Wilford, John Noble. Columbus’s lost town: new evidence is found. New York Times, Aug 27, 1985.

- [1] Anthropologist and museum professional.

- [2] Wall Street Journal: Duty-free entrance to the U.S. is “a big reason” behind Sae-A’s decision, Mr. Garwood said. It means that Sae-A will be able to offer discounts to U.S. clients, who will then have incentives to place more orders with the company, he said.…” This is business,” Mr. Garwood said. “At the end of the day, it’s about making a profit. It’s finding a country like Haiti with close proximity to the U.S. and having access to a labor supply. There’s such unemployment here there won’t be a problem finding employable people although it will take time and effort to train them.”

- [3] At least four studies have been commissioned: two by Koios, one by the Rocher group, and another by the University of Quisqueya, according to Haiti Grassroots Watch. But what use are they if the recommendations are not taken into account?

- [4] A plan has been provided by the Haitian Ministry of Finance, but, according to reports from Haiti Grassroots Watch, the farmers have not received any compensation.

- [5] Food for the Poor, is known as an organization through which the U.S. often passes on to the “Third World” the subsidized agricultural products of U.S. farmers.

- [6] Excavations unfortunately cut short after the political crises of 1986 and 2003-2004.

- [7] Full text in Koios report: p. 35 “In view of the selection criteria established by the Haitian government and cited in the previous section of this report, the possibility of finding another site that would be preferable to the one that was the subject of our analysis and would respond equally to those criteria, is unlikely. There are therefore only two alternatives to this project: 1. Moving the project to another site, or, 2. Cancellation of the project.”

- [8] Carl Henry Cadet. For an environmentally friendly park. Le Nouvelliste, Feb 8, 2012. http://lenouvelliste.com/article.php?PubID=1&ArticleID=102450&PubDate=2012-02-08, FoProBiM. Quis custodiet ipsos custodes? www.FoProBim.org

Center for Studies and Research on Cultures and Societies (CERDECS), Port-au-Prince, Haiti February 12, 2012, cerdecs@gmail.com

Sources: Haiti Chery (English translation, editorial comment, addition of photos) | AlterPresse (French)

Commentaire

anglais | français

Cet excellent article nous fournit une grande vue des impacts négatifs du projet du parc industriel dans le Baie de Caracol.

C’ est difficile de croire en la bonne volonté d’aucune personne associée à ce projet. Le rapport Koios, même si elle contient quelques vérités dans un souci de crédibilité, est une étude extrêmement biaisée, puisque Koios avait choisi le site en premier lieu, et l’étude a été commandée par la Banque Interaméricaine de Développement (BID), l’un des principaux bailleurs de fonds pour le projet.

Ceci fait partie d’une longue lignée d’études (pour la BID, la Banque mondiale, USAID, etc) dont le but véritable est d’évaluer l’impact d’un projet pour que le maximum de dégâts pourraient être infligés. Dans ce cas, tous les résultats servent à optimiser le travail dans les ateliers de misère.

- Plus d’un milliers de petits paysans ont déjà été dépossédés. L’objectif est de les transformer, avec leurs familles et leurs voisins en mains-d’œuvre les moins chères possible pour les ateliers de misère.

- Les sites naturels et archéologiques seront détruits de telle sorte qu’une source possible de revenus du tourisme se fasse disparaître.

- L’eau sera appropriée, polluée et rendue plus chère dans un pays qui souffre d’une pénurie d’eau potable et une épidémie de choléra. Et pourquoi? Pour que les travailleurs travaillent encore plus pour acheter de l’eau.

- L’aliment ubventionné américain sera vendu afin que ce qui reste de la production agricole du pays sera détruit et les travailleurs seront forcés de travailler jour et nuit pour s’acheter de la nourriture.

Oui. Le plan annoncé est faire marcher les machines à coudre 24 heures sur 24.

En plus d’être historiquement et archaelogiquement important, le site qui est prévu pour la destruction est un endroit d’une beauté extraordinaire et fait partie d’un écosystème naturel qui est unique à Haïti. Non seulement les Haïtiens, mais le monde entier sera appauvrie. Tout le monde devrait prendre connaissance de cette perte et faire tout en leur pouvoir pour l’arrêter.

Par Chery Dady, rédacteur en chef

Haïti Chery

Des choix économiques susceptibles de conduire à une autodestruction environnementale

Par Rachelle Charlier Doucet [1]

AlterPress

anglais | français

Notre propos, dans cet article, est de poser la question de la nécessaire articulation des choix économiques d’Haïti avec les exigences de protection de l’environnement naturel et culturel du pays, dans une perspective de respect des droits des ouvriers haïtiens et des droits économiques, sociaux, culturels et environnementaux de la population dans son ensemble.

Sans nier l’impact de ce projet pour la création d’emplois tellement nécessaires en Haïti, nous voudrions attirer l’attention sur les risques liés à l’implantation de ce futur parc, les dangers pour l’environnement en général et pour l’écosystème marin de la baie de Caracol en particulier.

Ces dangers concernent également le patrimoine culturel et le potentiel touristique dans les départements géographiques du Nord et du Nord-Est.

Une fois de plus, nous semblons donner raison à Jared Diamond, biologiste, professeur de géographie à l’université de Californie à Los Angeles (États-Unis d’Amérique).

Diamond pose le problème crucial du « développement durable et écologiquement soutenable » à travers les âges et cherche à comprendre les mécanismes par lesquels une société humaine emprunte la voie de l’autodestruction à court, moyen et long terme.

Développée dans son ouvrage retentissant Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed (effondrement), sa théorie est simple : il y a des sociétés qui choisissent d’échouer, il y en a d’autres qui choisissent de réussir.

Les premières ont épuisé leurs ressources naturelles et ont été incapables de reconnaître les moments, où des changements étaient devenus nécessaires à leur survie.

Les deuxièmes, par contre, sont parvenues à renverser leurs paradigmes culturels, à bousculer leur confortable routine et à prendre des mesures audacieuses qui ont assuré leur bien-être collectif.

Cinq (5) facteurs principaux sont à la base de ces « choix » et ils sont tant externes qu’internes.

Ce qui importe de retenir de l’analyse des comportements collectifs, faite par Diamond, c’est le rapport qu’il établit entre les besoins du groupe social, ses valeurs, les ressources du milieu et la vision de ses leaders.

Pour Diamond, un groupe, dans son ensemble, peut prendre de mauvaises décisions, en se basant sur des décisions individuelles erronées.

Diamond illustre sa thèse en prenant l’exemple de civilisations passées et aussi de sociétés contemporaines.

L’exemple passé, le plus parlant, est peut-être celui de l’île de Pâques (dans le Pacifique).

Cette société jadis florissante, vivant dans une végétation luxuriante, a connu un déclin lent, mais inexorable, parce que les préoccupations politiques et sociales ont pris le pas sur la préservation de l’environnement, souligne Diamond.

Les premiers Polynésiens de l’île ont coupé jusqu’au dernier arbre pour ériger des statues à leurs dieux, retient-on.

Le résultat du déboisement, prévisible sur le long terme, mais invisible du dedans et à court terme, a été atteint en quelques siècles : désertification et disparition du groupe humain établi sur l’île.

Pour les sociétés contemporaines, Diamond compare la République Dominicaine et la République d’Haïti. Vous aurez deviné dans quelles catégories respectives – succès ou échec – il place nos deux pays !

Haïti est le mauvais exemple à ne pas suivre et il lance une mise en garde sévère : « la plus grande menace pour le monde actuel est que des conditions pareilles à celles d’Haïti se généralisent dans le tiers-monde » ( Diamond 2005 : 499).

On peut, certes, critiquer Diamond pour un certain déterminisme écologique, et un regard, parfois superficiel et erroné, sur Haïti, mais il y a quand même des enseignements salutaires à tirer de ses réflexions.

Si sa comparaison avec la Dominicanie est instructive, il est encore plus productif pour nous, Haïtiennes et Haïtiens d’aujourd’hui, de comparer notre comportement environnemental avec celui des Polynésiens de l’Île de Pâques.

Les dévastations, causées par la tempête Jeanne en 2004 et les cyclones, Faye, Gustav, Hanna et Ike en 2008 – pour nous cantonner à un passé récent – devraient nous interpeller.

Le tremblement de terre du 12 janvier 2010 nous a remis face à notre grande vulnérabilité.

Avons-nous tiré les leçons qu’il faut ? Allons-nous enfin reconnaître qu’il est venu le temps d’agir et de changer de comportement ?

« En fonçant allégrement dans la construction d’un parc industriel à Caracol, ne sommes-nous pas en train de couper sciemment l’un de nos derniers arbres ? »

Une solution a court terme qui risque d’hypothéquer l’avenir

La création du parc industriel promet 20,000 emplois dans un premier temps, pour atteindre 60,000 à 80,000 d’ici quatre à cinq ans.

Cependant, le parc ne sera attractif que si Haïti parvient à maintenir son « avantage comparatif », basé sur une main-d’œuvre abondante, mais non qualifiée, et à qui l’on offrira de bas salaires. [2]

Comme le souligne le rapport, cet « avantage » est volatil : « en tant que pays, où les coûts de main-d’œuvre sont faibles, Haïti peut soutenir la concurrence dans le bas de gamme du marché à l’heure actuelle, mais cette situation ne persistera probablement pas indéfiniment. En effet, les coûts dans plusieurs autres pays sont d’ores et déjà compétitifs par rapport à ceux d’Haïti ».

Nous devrions soigneusement penser nos choix économiques et adopter une approche holistique.

Nous savons ce que cela veut dire, quand on veut transformer les agriculteurs haïtiens en salariés pour les usines de sous-traitance, sans peser les conséquences de la démarche dans une perspective globale.

Martelly disant qu’Haïti est «ouverte aux affaires» lors de l’inauguration du parc le 28 novembre 2011 (Photo: Page Facebook Michel Martelly).

Nous en avons fait l’expérience avec la « révolution économique » de Jean-Claude Duvalier et son projet de faire d’Haïti la « Taiwan dans les Caraïbes ».

Depuis la fin des années 1980, nous avons accéléré la destruction de la production nationale agricole « pour donner à manger au peuple à bon marché », en important du riz américain, et nous avons laissé les campagnes haïtiennes à l’abandon. Le président William Jefferson (Bill) Clinton [des Etats Unis] a reconnu publiquement les impacts néfastes de choix économique pour Haïti, basé sur des prémisses néolibérales erronées.

La création du parc de la société nationale des parcs industriels (Sonapi) à Port-au-Prince et la bidonvillisation qui s’en est suivie affectent encore toute la zone métropolitaine de la capitale.

Côté environnement nous avons assisté – impuissants ou insouciants – à la détérioration, sous nos yeux, de l’une des plus belles baies du monde (la troisième, dit-on, après celle de Rio et de Naples) avec ses montagnes avoisinantes et ses précieux bassins versants qui alimentent des sources aujourd’hui polluées et à débit réduit.

Port-au Prince aurait pu être la plus belle capitale dans les Caraïbes. Aujourd’hui Port-aux-Fatras, elle subit les conséquences de nos inconséquences.

L’exemple récent de la compagnie de développement industriel (Codevi) à Ouanaminthe (Nord-Est) est tout aussi parlant.

La création d’emplois, que promet le parc industriel de Caracol, ne va pas sans risques, selon ce que révèlent les rapports commandités par le ministère des finances et la banque interaméricaine de développement (Bid) et publiés en mai 2011 [3].

Les dangers, identifiés par le rapport Koios, sont nombreux et graves. En voici quelques-uns.

Il faudra d’abord effectuer le défrichage du parc, situé sur les meilleures terres arables et irriguées de la zone, et délocaliser 1,000 agriculteurs et leurs familles [4].

Ce parc sera la cause de grands stress sur les infrastructures sociales et urbaines, provoquera une migration estimée entre 30,000 à 300,000 personnes. Il exercera donc une pression démographie énorme sur les ressources disponibles.

Pour les seuls besoins de fabrication et de teinture du textile, il faudra pomper 6,000 m3 d’eau par jour dans la nappe phréatique – ce qui pourrait compromettre la recharge aquifère – et rejeter les eaux usées –mais traitées, on veut bien l’espérer ! – dans la rivière du Trou du Nord et, au final, dans la baie de Caracol.

L’électricité ne sera pas verte – opportunité ratée d’innover -, mais plutôt se produira au mazout, d’où des déchets lourds et toxiques.

La construction de 5,000 logements, par le gouvernement américain en partenariat avec Food for the Poor [5] ne pourra pas conjurer le danger de bidonvillisation, non seulement de Caracol, mais des localités avoisinantes.

La liste est longue : des risques et impacts négatifs, énumérés dans le rapport.

Nous voudrions insister sur deux aspects des risques, liés au projet de Caracol, qui devraient retenir notre attention.

Le rapport établit clairement les dangers pour l’environnement en général et l’écosystème marin en particulier. Il mentionne rapidement les dangers pour le patrimoine culturel et le potentiel touristique de la région Nord.

Sur le premier aspect, on lit ceci dans le rapport Koios :

Sur le premier aspect, on lit ceci dans le rapport Koios :

“La baie de Caracol est reconnue comme une zone unique à Haïti. Elle comprend les plus grandes mangroves restantes du pays, accueille plus de 20,000 oiseaux migrateurs par an et représente un habitat et une zone d’alevinage productifs pour un écosystème marin qui fournit de nombreux services aux communautés côtières haïtiennes.

Le gouvernement a d’ailleurs proposé d’en faire la prochaine aire protégée du pays. Un autre site serait une meilleure solution pour éviter les impacts sur des endroits sensibles tels que la Baie de Caracol.

Si un autre site n’est pas disponible, un plan de conservation et de gestion, soutenu et appliqué rigoureusement, doit être mis en place.”

En plus de leur rôle irremplaçable dans le maintien de l’équilibre écologique marin, les mangroves jouent également un rôle de protection en cas de tsunami et de cyclones. Ce que ne signale pas le rapport Koios.

“ Le potentiel touristique de la zone et de la région environnante est considérable, car on peut y trouver certains sites historiques clés, tels que le parc national historique Sans Souci, la Citadelle Ramiers (sic) et la Citadelle Henri. La Navidad, où Christophe Colomb aurait débarqué la première fois et Puerto Real (sic), dans la baie de Caracol (le premier port commercial connu du Nouveau Monde) s’y trouvent également. Bien que ces sites culturels ne soient pas directement touchés par le projet, il est important de planifier et d’évaluer le parc industriel dans le contexte régional plus large des plans régionaux et du potentiel de la région », souligne le rapport Koios sur le volet patrimoine culturel et touristique.

Nous voudrions prendre le contrepied de la dernière affirmation, à savoir que ces sites ne seront pas touchés directement par le projet.

Nous pouvons aisément prévoir les effets d’une migration non contrôlée de 300,000 personnes sur les paysages naturels et culturels de toute la région, et surtout sur les sites situés aux alentours immédiats de Caracol.

Or, c’est le cas pour La Nativité (ou La Navidad en espagnol) et Puerto Real.

Il faut préciser que les traces du fortin La Navidad, érigé le 24 novembre 1492 sur les instructions de Colomb – suite au naufrage de la Santa Maria -, ont été identifiés à En-Bas Saline, à seulement un kilomètre de Caracol.

C’est, donc, chez nous que se trouve la première fortification du Nouveau Monde. Nous pouvons revendiquer son existence et la vendre comme un produit touristique d’un intérêt certain.

C’est, donc, chez nous que se trouve la première fortification du Nouveau Monde. Nous pouvons revendiquer son existence et la vendre comme un produit touristique d’un intérêt certain.

Ce fortin, érigé au milieu du village taino de Guacanagaric, a été détruit par les tainos, mais des traces et l’emplacement subsistent.

En outre, des fouilles archéologiques, menées par l’université de Floride à Gainsville et le bureau d’ethnologie [6], ont révélé que le village taino de Guacanagaric, vieux déjà de 300 ans à l’arrivée de Colomb, est l’un des plus grands et plus complets dans les Caraïbes.

Il est aujourd’hui recouvert d’herbes folles et livré en pâture aux cabris.

Par ailleurs, la « cité perdue » de Christophe Colomb, la fameuse ville de Puerto Real, longtemps restée une énigme pour l’archéologie dans les Caraïbes, a été retrouvée, grâce au Dr. William Hodges, non loin de Caracol, à environ 2 km de En-Bas Saline.

L’importance de Puerto Real, pour l’histoire de la colonisation et l’émergence de cultures créoles, est d’un intérêt scientifique indiscutable.

Les artefacts, recueillis par l’équipe de la Dre. Kathleen Deagan, ont permis d’identifier des phases et des mécanismes de créolisation entre les cultures taino, hispaniques et africaines. Les trois cultures y ont coexisté entre 1503 et 1578.

Sur ce lieu hautement important et symbolique, devrait être érigé un musée ou un centre d’interprétation historique.

Le site ne devrait pas retomber tout doucement dans l’oubli, ou pire vandalisé par de futurs squatters.

Donc, dans un rayon de 2 km de Caracol, nous trouvons trois sites archéologiques importants et d’une valeur historique et culturelle inestimable : le village taino de Guacanagaric, le fortin de la Nativité et la ville hispanique de Puerto Real.

Qui dit mieux, comme atout touristique ?

Tout le quadrilatère « Limonade / Caracol / Trou-du-Nord / Fort Liberté » devrait être classé patrimoine national et protégé.

En dehors de l’aspect historique, les baies de Caracol et de Fort-Liberté (Bayaha en taino) sont des sites d’une époustouflante beauté qui devraient se prêter au tourisme écologique !

Et on voudrait les détruire !

Les termes de l’équation

La situation est donc on ne peut plus claire.

L’ingénieur-agronome Ronald Toussaint, actuel ministre démissionnaire de l’environnement (Mde), lors d’une rencontre organisée le 8 février 2012 à l’est de la capitale, a dû l’admettre devant les bailleurs et ses invités : tout l’écosystème « précieux et unique de la baie de Caracol » est en danger par l’implantation du parc industriel, précisément à cet endroit-là.

L’étude de la compagnie Koios, engagée pour évaluer les impacts sociaux et économiques après le choix du site (oui, comme toujours, nous mettons la charrue avant les bœufs), même si elle peut être prise à défaut pour négligences et erreurs méthodologiques graves, donne, cependant, un avis clair : vu les menaces certaines sur les infrastructures sociales et physiques locales, et en particulier sur l’environnement et l’écosystème marin de la baie,

« l’alternative laissée au gouvernement est ou bien d’annuler, ou bien de relocaliser le parc » …

« Le choix, évidemment, n’est pas technique mais politique » [7] (Koios 2011 : 35 ).

Plus loin, prenant en compte des considérations« d’ordre politique », le même rapport nuance sa position.

Le mot « politique » – on le comprend – est pris ici dans un sens étroit, qui concerne, non pas les « affaires de la cité », donc de la nation, mais bien les intérêts de certains groupes puissants, locaux et internationaux.

Ces considérations « politiques » se lisent comme suit :

“ Il serait possible d’annuler carrément le projet, mais les enjeux sont majeurs.

En premier lieu, le projet de parc industriel de la région du Nord-Est d’une grande visibilité, grâce à la participation de la Bid, du gouvernement des États-Unis d’Amérique, et d’un grand groupe sud-coréen, ainsi qu’à la grande publicité qui accompagne le projet depuis plusieurs mois. Son annulation pourrait mettre en jeu la réputation de ces parties prenantes et pourrait nuire à la réputation d’Haïti comme un pays accueillant à l’investissement”.

Ce qui amène la firme Koios à proposer d’autres choix au gouvernement, en particulier surseoir à l’exécution pour mener des études scientifiques et élaborer des plans de gestion axés sur le fonctionnement et les impacts du parc, ainsi que sur l’établissement d’un cadre de politiques et de normes, auxquelles tous les occupants du parc devront se conformer.

Mais, le rapport ajoute ce bémol important :

« Les bonnes pratiques standard de gestion ne peuvent pas atténuer ces impacts facilement ou à peu de frais. Les mesures nécessaires impliqueront, non seulement la sensibilisation du public, mais aussi des dépenses en capital ».

Plan de gestion et mesures de mitigation indispensables

Il faudrait au ministère de l’environnement environ 50 millions de dollars américains [Ndlr : US $ 1.00 = 42.00 gourdes ; 1 euro = 61.00 gourdes aujourd’hui] pour un plan de mitigation de ces risques, selon le ministre Toussaint.

Or, à date, le Mde n’a trouvé que 4,2 millions de dollars [8].

Que va-t-il se passer si les fonds ne sont pas disponibles et si les recommandations, contenues dans les différents plans de gestion, ne peuvent pas être mises en pratique ?

Nous connaissons la réponse : très probablement RIEN.

Et c’est là la raison de notre inquiétude.

Au vu de notre insouciance passée, du manque de sensibilisation de la population et des plus hautes instances de l’État sur les questions environnementales et patrimoniales, et surtout vu le manque d’infrastructures légales et administratives, et les carences actuelles en ressources matérielles, humaines et financières, avons-nous de bonnes raisons de croire que toutes les mesures seront prises pour faire face à tous les problèmes mentionnés, et ce avant l’ouverture du parc, prévu pour fin mars 2012 ?

On attend donc de nous, citoyennes et citoyens haïtiens, ou bien une confiance aveugle dans les femmes / hommes politiques et les femmes / hommes d’affaires de ce pays et une foi béate dans la bienveillance internationale, ou bien on nous force à adopter une mentalité « magique », qui nous permettrait d’affirmer que, dans ce « singulier petit pays », les mêmes causes ne produisent plus les mêmes effets.

Tout ira bien, les choses s’arrangeront d’elles-mêmes.

Nous avons une propension à classer tout avertissement, basé sur des données scientifiques, au rang d’élucubrations fantaisistes d’une poignée de lunatiques.

Dans notre incrédulité et notre insouciance proverbiales, le concept « catastrophe prévisible » est tout simplement inconcevable.

Nous sommes en Haïti, vous savez…au pays du Bon Dieu deux fois Bon.

Conclusion

« Notre conclusion est que le projet aura une incidence sur des habitats naturels critiques, s’il est établi à cet endroit (…) La question, qui reste à déterminer, est de savoir si le projet [est de nature à] changer ou dégrader des habitats naturels critiques de manière significative.” (rapport Koios 2011 : p.126).

Non, la vraie question n’est pas de savoir si l’impact va être significatif ou pas.

La réponse, nous l’aurions trop tard !

Le vrai problème, c’est qu’il y aura un impact certain, et à moins d’un miracle, nous n’aurons pas les moyens d’y faire face.

En effet, comment penser autrement, quand nous mettons en regard nos forces et nos faiblesses, en termes de gestion rigoureuse, de suivi et de monitoring des dossiers de l’État ?

Dans l’état actuel des choses, le dilemme, c’est comment saisir équitablement les opportunités économiques à court terme, offertes par le futur parc de Caracol, sans compromettre à tout jamais le patrimoine naturel et culturel de toute la région ?

Ensemble, milieux académiques, organisations sociales de tout le pays, investisseurs, gouvernement et bailleurs, nous devons, par la réflexion et la concertation la plus large possible, arriver à des solutions gagnant-gagnant.

Tout en reconnaissant les impératifs économiques de l’heure, nous devons nous mobiliser pour empêcher la destruction irréparable et irréversible de ces richesses nationales.

C’est pourquoi le centre d’études et de recherche sur les cultures et sociétés (Cerdecs) lance les appels suivants, non pas pour annuler le projet – ce serait irréaliste, vu l’état d’avancement des travaux – mais, au moins, pour obtenir un engagement ferme des parties prenantes, afin de prévenir et limiter les dommages collatéraux qui affecteront la population et son milieu de vie.

- – Appel au gouvernement, pour surseoir à l’implantation du parc industriel à Caracol, tant que les points importants – soulevés quant aux risques – ne seront pas adéquatement abordés et que les ressources – matérielles et financières pour la protection du patrimoine naturel et culturel en danger – ne seront pas clairement identifiées et dégagées ;

- – Appel à l’exécutif et au parlement, pour monter un appareil législatif qui aborde, de manière exhaustive et rigoureuse, la dégradation de notre environnement ;

- – Appel au ministère de l’environnement et au parlement, pour la constitution d’une zone protégée, bien au-delà du parc marin de Caracol, qui inclura aussi la baie de Fort Liberté ;

- – Appel au parlement, pour la ratification des traités et conventions, sur la protection du patrimoine, non encore ratifiés ;

- – Appel au ministère de la culture et de la communication (Mcc), à la secrétairerie d’État du patrimoine, au bureau d’ethnologie et à l’institut de sauvegarde du patrimoine national (Ispan) pour le classement des sites archéologiques précolombiens et hispaniques, déjà identifiés dans tout le pays comme patrimoine national ;

- – Appel au ministère de la culture et de la communication, à la secrétairerie d’Etat du patrimoine, au bureau d’ethnologie, à l’Ispan et à International council on monuments and sites / Conseil international des monuments et sites (Icomos-Haïti), pour l’inscription urgente de l’ensemble de sites archéologiques, précolombiens et hispaniques de l’île, à la liste du patrimoine mondial (conjointement avec la République Dominicaine). L’ensemble comprend 24 sites pour l’île entière, dont 10 sont situés en territoire haïtien ;

- – Appel aux instances concernées (ministère de la culture et de la communication, secrétairerie d’État du patrimoine, Ispan, Icomos-Haïti), pour initier – si ce n’est déjà fait – les démarches d’inscription des paysages culturels du Grand Nord sur la liste indicative du patrimoine mondial de l’organisation des Nations Unies pour l’éducation, la science et la culture (Unesco) ;

- – Appel au ministère du tourisme, à l’association hôtelière et touristique d’Haïti et à celle du Nord, aux organisations locales d’éco-tourisme, afin de valoriser ce patrimoine unique. L’on pourrait, entre autres, créer la « Route de Colomb-Haïti » qui irait du Môle St Nicolas à la Baie de Mancenille. Une « Route de Colomb-Hispaniola » pourrait aller du Môle St-Nicolas à la presqu’île de Samana (sur la base du premier voyage de Colomb). Cette dernière initiative devrait être étudiée conjointement avec la République Dominicaine ;

- – Appel aux universités haïtiennes, et en particulier à l’université de Limonade, pour la création de programmes en océanographie, biologie marine, sciences environnementales, archéologie, muséologie et formation aux techniques et métiers du patrimoine et du tourisme. En plus de leur intérêt scientifique certain, ces connaissances et compétences sont indispensables pour le développement d’un secteur culturel et touristique fort, et surtout, respectueux de l’environnement ;

- – Appels aux bailleurs et aux investisseurs, pour qu’ils s’engagent, résolument et sans équivoque, et par des actions concrètes, à prendre en compte la problématique environnementale dans leurs projets en Haïti ;

- – Appels aux groupes écologistes du pays et de l’extérieur, pour la défense de ce patrimoine naturel unique et irremplaçable pour Haïti, les Caraïbes et la planète toute entière.

Nous faisons nôtre le cri d’alarme de la fondation pour la protection de la biodiversité marine, qui « réitère ses profondes préoccupations » et lance un appel à

« tous les bailleurs de fonds internationaux participants (qui) sont liés par des procédures de protection environnementale qu’ils doivent respecter.

Ne laissez pas ceci devenir un autre exemple de projet lancé à la course, sans que les protections environnementales appropriées ne soient mises en place. Haïti ne peut [point] se permettre des désastres environnementaux supplémentaires ».

Appuyons la mise en garde courageuse du ministère de l’environnement d’Haïti, comprenons que des études scientifiques et des actions de mitigation et de sauvegarde multisectorielles sont indispensables et urgentes comme préalable à la mise en œuvre du projet.

Sinon, le parc industriel de Caracol sera à inscrire au livre rouge des catastrophes écologiques annoncées.

Références

- – AlterPresse Haïti-Parc industriel de Caracol : Un modèle, pour Michel Martelly. Silence sur les impacts négatifs… 29 novembre 2011 / Ayiti Kale Je. Le parc industriel à Caracol: Une situation ‘gagnante-gagnante’ pour tous ?

- – BID Communique de presse 28 novembre 2011. www.iadb.org

- – Cadet , Carl Henry. Pour un parc respectueux de l’environnement. Le Nouvelliste, mercredi 8 février 2012.

- – Deagan, Kathleen (editor). Puerto Real : The Archaeology of a Sixteenth Century Spanish Town in Hispaniola. University Press of Florida, Gainesville, 1995.

- – Deagan, Kathleen. Curation of materials from En Bas Saline. Florida Museum of Natural History. En Bas Saline Project, 2003

- – Diamond, Jared. Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed. New York : Penguin Books. 2005.

- – FoProBiM. (Fondation pour la Protection de la Biodiversité Marine) Quis custodiet ipsos custodes ? www.FoProBim.org

- FoProBiM (Fondation pour la Protection de la Biodiversité Marine) et ReefFix Rapid Assessment of the Economic Value of Ecosystem Services Provided by Mangroves and Coral Reefs and Steps Recommended for the Creation of a Marine Protected Area, Caracol Bay, Haïti May, 2009 For the Organization of American States (OAS) and the Inter-American Biodiversity Information Network (IABIN). www.foprobim.org

- – Joachim, Dieudonné Le Nouvelliste, Haïti : Caracol aura le plus grand Parc industriel du pays 28 nov 2011 http://lenouvelliste.com/article.php?PubID=1&ArticleID=99788&PubDate=2011-11-28

- – KOIOS Associates LLC. Étude des Impacts Environnementaux et Sociaux (EIES) du Parc Industriel dans la Région du Nord d’Haïti présenté au Ministère de l’Économie et des Finances de la République d’Haïti, 21 juin, 2011.

- – MEF-UTE et Bid. Contrat HA-L1055-SN2. Plan d’Action pour la compensation et le rétablissement des moyens d’existence des personnes affectées par le projet du parc industriel de la région du nord. Réalisé par ERICE AZ, PauP Sept 2011

- MEF-UTE : www.ute.gouv.ht/caracol/imag…,

- – PIRN . Plan de Gestion Environnemental et Social (PGES) pour Le Parc Industriel de la Région du Nord d’Haïti. 5 août 2011.diamond

- – Wall Street Journal. Planned haitian textile park provides hope for jobs. 11 Janvier 2011. Wilford, John Noble . Columbus’s lost town : new evidence is found. New York Times. August 27, 1985

- [1] Anthropologue et muséologue.

- [2] Wall Street Journal : Duty-free entrance to the U.S. is “a big reason” behind Sae-A’s decision, Mr. Garwood said. It means that Sae-A will be able to offer discounts to U.S. clients, who will then have incentives to place more orders with the company, he said.( …) “This is business,” Mr. Garwood said. “At the end of the day, it’s about making a profit. It’s finding a country like Haiti with close proximity to the U.S. and having access to a labor supply. There’s such unemployment here there won’t be a problem finding employable people although it will take time and effort to train them.”

- [3] Au moins quatre études on été commanditées : deux attribuées à la firme Koios, l’une au groupe Rocher, l’autre à l’Universite Quisqueya, selon le dossier de Ayiti Kale Je. Mais à quoi servent-elles si les recommandations ne sont pas prises en compte ?

- [4] Un plan a été prévu par le ministère des finances haïtien, mais, selon les reportages de Ayiti Kale Je, les agriculteurs n’ont encore reçu aucune compensation.

- [5] Food for the Poor, connu pour être un organisme à travers lequel les États-Unis d’Amérique écoulent, souvent vers le “Tiers-Monde”, les produits agricoles de leurs fermiers, lesquels sont subventionnés.

- [6] Fouilles malheureusement interrompues suite aux troubles politiques de 1986 et 2003-2004.

- [7] Texte intégral du rapport Koios : 35 « En vue des critères de sélection établis par l’État haïtien et cités dans la section précédente de ce rapport, la possibilité de trouver un autre site, préférable à celui qui a fait l’objet de notre analyse et qui répondrait, de façon égale, à ces critères, est peu probable. Il n’existe donc que deux alternatives au présent projet : 1. déplacement du projet dans un autre lieu ; ou, 2. annulation du projet. »

- [8] Carl Henry Cadet. Pour un parc respectueux de l’environnement. Le Nouvelliste, mercredi 8 février 2012, FoProBiM. Quis custodiet ipsos custodes ? www.FoProBim.org

Rachelle Charlier Doucet, Centre d’études et de recherche sur les cultures et sociétés (Cerdecs), Port-au-Prince, le 12 février 2012, cerdecs@gmail.com

Sources: AlterPresse

Comments

Caracol Free-Trade Zone Jeopardizes Natural and Cultural Heritage | La zone franche de Caracol met en péril le patrimoine naturel et culturel du Nord-Est — No Comments