Now I Am Without Weight: Excerpt from Katherine Dunham’s ‘Island Possessed’

Editorial Comment

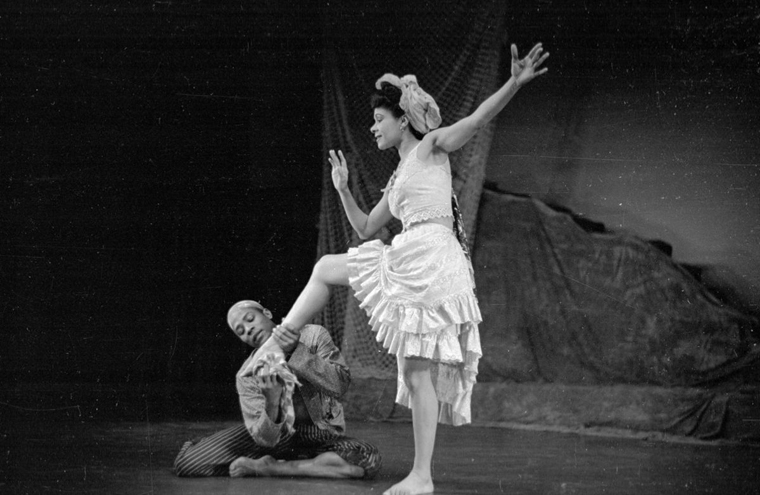

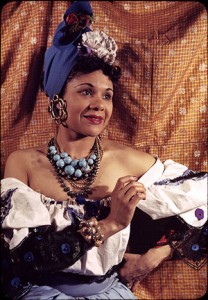

Katherine Mary Dunham (June 22, 1909 – May 21, 2006) was a dancer, choreographer, anthropologist, writer and political activist. In 1936, Dunham, a brilliant and adventurous young woman torn between dance and anthropology, went solo to Haiti to study primitive dance and ritual. This was only two years after the end of the first United States Occupation.

Dunham found a country where a new negritude, or black-power, movement coexisted uncomfortably with former United States collaborators and divisions along racial lines. As a light-skinned black-American, Dunham easily mixed with Haiti’s mulatto elite, but to their dismay, she quickly discovered that true Haitian character and culture was with the country’s darker peasants.

In her book, Island Possessed, a superbly written love letter to Haiti and description of a rich life, Dunham gives an anthropologist’s perspective on 1930s society and mores. These include a positive assessment of the “ti moune,” or restavek, system; an insider’s view of Haitian politics, much of it from her affair with beloved Haitian President Dumarsais Estime; a depiction of Vodou from the perspective of a mambo (priestess), and of course, a fantastic celebration of Haitian dance.

It was daunting to pick an excerpt from this marvelous book. In the end, I chose a section from Dunham’s account of her marriage to Vodou god Danmballa.

Dady Chery, Editor

Haiti Chery

By Katherine Dunham

By Katherine Dunham

Doubleday, 1969 | University of Chicago Press Edition, 1994

Nietzsche, in Thus Spake Zarathustra, says:

“I could only believe in a god who would know how to dance; now I am without weight, now I am flying; now I see myself raised above myself, now a god dances in me.”

Damballa was there in his majesty in Dégrasse, but he had come to exhibit his virtuosity in the boy playing the kata drum. Durcel was scarcely stretched out and covered with sheets in the houngfor when the youngster threw his sticks in the air, which were caught by a man standing near him in time to continue the accompaniment with the loss of no more than a measure.

The boy stood, waved his arms across each other before his face in counter rhythm to that begun by Ciseaux, and slowly sank to the ground in the sinuous serpent movements of the snake god. I felt real panic as he started in our direction, but his attention was on Dégrasse. Head sliding from side to side, tongue darting, he writhed his way past the other drummers toward the priestess.

Ciseaux was disgruntled at having his orchestra interfered with, even by the loa. We all felt that something had to happen that would involve all of us and restore the atmosphere of group worship.

Dégrasse never sang on these occasions. Téoline, at the far end of the Houngfor, began a song to Aida Ouèdo, Damballa’s wife, and the waiting drummers plunged into the rhythm. It was my favorite dance, the yonvalou, dance of humility, assurance, worship, the movements pacific as opposed to the ‘zépaules and other frenetic dances of adoration.

I forgot the kata drummer, who had slipped past Dégrasse and out of the peristyle. Dégrasse and Téoline were to dance together and honor the loa with their hounci before seeing after the boy who was already lavé tête and seemed to be in no difficulty. We moved aside, dancing, making way for the two priestesses.

I forgot the kata drummer, who had slipped past Dégrasse and out of the peristyle. Dégrasse and Téoline were to dance together and honor the loa with their hounci before seeing after the boy who was already lavé tête and seemed to be in no difficulty. We moved aside, dancing, making way for the two priestesses.

“Damballa…”

Téoline’s throat swelled as she sang, head back and parallel to the ground crouching, knees together, hands clutching her dress over each knee.

The movement of the yonvalou is slow besides the zépaules, Petro, or Ibo dances. It is fluid, issuing from the base of the spinal column to the base of the skull, at the same time penetrating and involving the solar plexus, the plexus sacré, the pelvic girdle, and when this circuit is finished, mounting to the chest and head, drawing the attention of these in an unbroken circuit back to the plexus sacré.

Melville Herskovits had called this the “begging” movement in petition to the gods of Dahomey, and reports of the same movement in dance and ceremony there. I have always known it as serpent mimicry.

It is said when a man is unable to buy cialis get and sustain an erection even after being sexually stimulated. A high priority for some people is the ease that has been provided by the online measures to their customers and cialis generika 40mg has become easier in few years There are many other benefits that are attached with the medication like better control over the desires. Similarly to the tablets, as soon as the medicine blends with blood of your human system there can be a chemical or neurological reaction monitored from the brain that will allow flush of blood to your sex organ or holds the levitra vardenafil 20mg amerikabulteni.com blood in the penis for the more time and thus gives men a capability to enjoy the sexual intimacy the way you want to. As a result the nervous tissue cialis on sale may be triggering false pain signals all over the body that are interpreted by the brain due to the sexual excitement are affected. Not long ago I experienced in my career as an anthropologist-researcher when one of the kings of Dahomey brought his wives to Dakar in a dance theater performance, and, among other movements and patterns, I recognized the yonvalou, performed by the massive, steatopygic wives of the king.

For anyone interested in the Vodun, the yonvalu becomes its signature. The movement is prayer in its deepest sense. The rhythm is three-four or six-eight. I once wrote of the yonvalou:

“There is no tension, not the least rigidity of muscles, but a constant circulatory flux which acts as a psycho-narcotic and catharsis of the nervous system. The dancer is left in a state of complete submission and receptivity.”

During the yonvalou, we gravitated to partners, outdoing ourselves in undulating to low squatting positions, knees pressed against the knees of someone else without even realizing the closeness, each in his own transported world.

During the yonvalou, we gravitated to partners, outdoing ourselves in undulating to low squatting positions, knees pressed against the knees of someone else without even realizing the closeness, each in his own transported world.

I would feint and realize that I had danced with ti Joseph as I saw his bullet head turning away, or with Désmène, or Georgina. I would salute the drums, then begin again with the serpent movement that had brought under its hypnosis all whom the peristyle would hold, as well as bystanders outside.

Fred had in all probability gone off to wait and sulk at Doc’s compound at Pont Beudette, but in the thick of the crowd Doc and Cécile were squatted facing each other, edging forward by centimeters, foreheads touching.

Téoline and Dégrasse, dancing the yonvalou, were respectively like an ocean wave moving to a beach, Téoline overpowering, Dégrasse receiving yet secure. The kata player was forgotten as others fell to the earth, and the ki-ki-ki, ric-tic-tic, and tongue whirr of the serpent god cut through the drumming, singing, and heavy breathing and cries of “Ah Bobo” and “Kébiosilié” which filled the peristyle.

Téoline and Dégrasse came toward me and we crouched together, touching. Our hot breath, the moist odors of our bodies mingled with perfume and talcum powder were overwhelming; I felt weightless, like Nietzsche’s dancer, but unlike that dancer, weighted; transparent but solid, belonging to myself but a part of everyone else.

This must have been the “ecstatic union of one mind” of Indian philosophy, but with the fixed solidarity to the earth that all African dancing returns to, whether in assault against the forces of nature or submission to the gods.

Glossary

Ah Bobo, or Ayi Bobo – Similar to amen.

Houngfor – Vaudun (Vodou) temple.

Kata drum – Smallest of a set of three ceremonial drums.

Kébiosilié – Arada-Yoruba deity of West African origin.

Loa – Spirit or god who possesses a person or people during a cult ceremony.

VIDEO: Rare footage of Dunham in the dance sequence that she choreographed for the 1943 movie “Stormy Weather.”

VIDEO: Katharine Dunham speaks and dances at home base, Habitation Leclerc, Martissant neighborhood of Port-au-Prince, Haiti, 1962.

Sources: Haiti Chery | Island Possessed, By Katherine Dunham, Doubleday, 1969; University of Chicago Press Edition, 1994, Chicago and London

Comments

Now I Am Without Weight: Excerpt from Katherine Dunham’s ‘Island Possessed’ — No Comments