Mithra: The Pagan Christ

By S. Acharya and D. M. Murdock

Truth Be Known

The following article is adapted from a chapter in Suns of God: Krishna, Buddha and Christ Unveiled, as well as The ZEITGEIST Sourcebook and articles such as The Origins of Christianity.

- “Both Mithras and Christ have been described variously as the way, the truth, the light, the life, the word, the son of God, the good shepherd.

- The Christian litany to Jesus could easily be an allegorical litany to the sun god.

- Mithras is often represented as carrying a lamb on his shoulders, just as Jesus is.

- Midnight services were found in both religions.

- The virgin mother… was easily merged with the virgin mother Mary.

- Petra, the sacred rock of Mithraism, became Peter, the Christian Church’s foundation.”[13]

– Gerald Berry, Religions of the World

- “Mithra or Mitra is… worshipped as Itu (Mitra | Mitu | Itu) in every house of the Hindus in India. Itu is considered to be the vegetation deity. Mithra or Mitra (sun-god) is believed to be a mediator between God and man, between the sky and the earth.

- It is said that Mithra or [the] sun took birth in a cave on December 25.

- It is also the belief of the Christian world that Mithra or the sun-god was born of [a] virgin.

- He traveled far and wide.

- He has twelve satellites, which are taken as the Sun’s disciples….

- [The sun’s] great festivals are observed in the winter solstice and the vernal equinox—Christmas and Easter.

- His symbol is the lamb….”[32]

– Swami Prajnanananda, Christ the Saviour and Christ Myth

Special attention should be paid to Mithraism, because of the evident relationship of this Persian-Roman religion to Christianity. Worship of the Indo-Persian god Mithra dates back centuries to millennia. The same god is Mitra in the Indian Vedic religion, which is over 3,500 years old by conservative estimates. After the Iranians separated from their Indian brethren, Mitra became Mithra or Mihr, as he is also called in Persian.

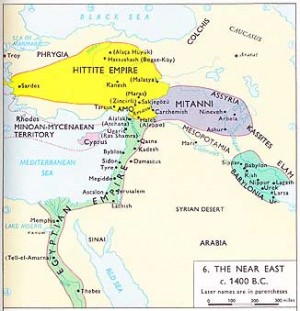

By 1500 BC, Mitra worship had made it to the Near East, in the Indian kingdom of the Mitanni, which was occupying Assyria. This worship was known as far west as the Hittite kingdom, only a few hundred miles east of the Mediterranean, as evidenced by the Hittite-Mitanni tablets discovered at Bogaz-Köy in what is now Turkey. The gods of the Mitanni included Mitra, Varuna and Indra, all found in the Vedic texts.

Mithra as sun god

The Indian Mitra represented the sun’s friendly aspects. The Persian Mithra was a benevolent god and the bestower of health, wealth and food. Mithra also seems to have been regarded as a sort of Prometheus, for the gift of fire.[38] His worship purified and freed the devotee from sin and disease. Eventually, Mithra became more militant and a warrior.

Like so many gods, Mithra was considered to be the light and power behind the sun. In Babylon, Mithra was Shamash, the sun god; he was also Bel, the Mesopotamian and Canaanite-Phoenician solar deity, who was likewise Marduk, the Babylonian god who represented both the sun and Jupiter. According to Pseudo-Clement of Rome’s debate with Appion, Mithra was also Apollo. [Homily VI, ch. X]

Mithra wears a crown of sun rays; Taqwasân or Taq-e Bostan or Taq-i-Bustan, Sassanid Empire, Coronation of Ardeshir II, c. 4th century AD/CE (Photo: Phillipe Chavin).

In time, Babylonians and Chaldeans infused Persian Mithraism with their astro-theology, and Mithraism became notable for its astrology and magic. Indeed, its priests, or magi, lent their very name to the word magic. This astro-theological development reemphasized Mithra’s early Indian role as a sun god.

In Forerunners and Rivals in Christianity, Francis Legge writes: “The Vedic Mitra was originally the material sun itself, and the many hundreds of votive inscriptions left by the worshippers of Mithras to the unconquered Sun Mithras, to the unconquered solar divinity (numen) Mithras, to the unconquered sun-god (deus) Mithra, and allusions in them to priests (sacerdotes), worshippers (cultores), and temples (templum) of the same deity leave no doubt open that he was in Roman times a sun-god.” [Legge, II, 240]

To the Roman legionnaires, Mithra — or Mithras, as he began to be known in the Greco-Roman world — was “the divine Sun, the Unconquered Sun.” He was said to be “Mighty in strength, mighty ruler, greatest king of gods! O Sun, lord of heaven and earth, God of Gods!” Mithra was also deemed to be the mediator between heaven and earth, a role often ascribed to the god of the sun.

An inscription in Rome by a T. Flavius Hyginus, from around 80 to 100 AD, which dedicates an altar to Sol Invictus Mithras | The Unconquered Sun Mithra, reveals the hybridization reflected in other artifacts and myths. Dr. Richard L. Gordon remarks: “It is true that one… cult title… of Mithras was, or came to be, Deus Sol Invictus Mithras (but he could also be called… Deus Invictus Sol Mithras, Sol Invictus Mithras…” …Strabo, basing his information on a lost work, either by Posidonius (ca 135-51 BC) or by Apollodorus of Artemita (first decades of 1 BC), states baldly that the Western Parthians “call the sun Mithra.” The Roman cult seems to have taken this existing association and developed it in their own special way. [8,21,23]

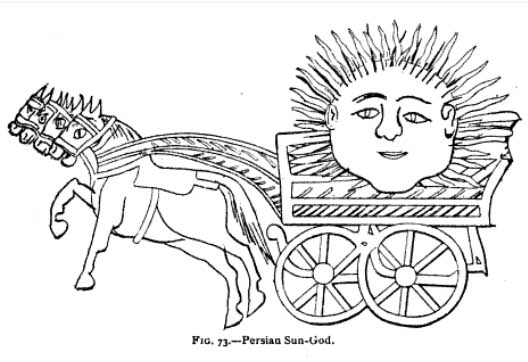

As concerns Mithra’s identity, Dr. Roger Beck says: “Mithras… is the prime traveler, the principal actor… on the celestial stage which the tauctony [bull-slaying] defines…. He is who the monuments proclaim him — the Unconquered Sun.”[12] In an early image, Mithra is depicted as a sun disc in a chariot drawn by white horses, another solar motif that made it into the Jesus myth, in which Christ is to return on a white horse. [Rev 6:2; 19:11]

Mithra in the Roman Empire

Subsequent to the military campaign of Alexander the Great in the fourth century BC, Mithra became the favorite deity of Asia Minor. Christian writers Dr. Samuel Jackson and George W. Gilmore, editors of The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge (VII, 420), remark: “It was probably at this period, 250-100 BC, that the Mithraic system of ritual and doctrine took the form which it afterward retained. Here it came into contact with the mysteries, of which there were many varieties, among which the most notable were those of Cybele.”[29]

According to the Roman historian Plutarch (c. 46-120 AD), Mithraism began to be absorbed by the Romans during Pompey’s military campaign against Cilician pirates around 70 BC. The religion eventually migrated from Asia Minor through the soldiers, many of whom had been citizens of the region, into Rome and the far reaches of the Empire. Syrian merchants brought Mithraism to the major cities, such as Alexandria, Rome, and Carthage, while captives carried it to the countryside. By the third century AD, Mithraism and its mysteries permeated the Roman Empire and extended from India to Scotland, with abundant monuments in numerous countries that amount so far to over 420 discovered Mithraic sites.

From various discoveries, including pottery inscriptions and temples, we know that Roman Mithraism gained a significant boost and much of its shape between 80 and 120 AD, when the first artifacts of this particular cultus begin to be found at Rome. It reached a peak during the second and third centuries, before largely expiring at the end of the fourth to the beginning of the fifth century.

Among its members during this period were emperors, politicians and businessmen. Indeed, before Mithraism’s usurpation by Christianity, it enjoyed the patronage of some of the most important individuals in the Roman Empire. In the fifth century, the emperor Julian, having rejected his birth religion of Christianity, adopted Mithraism and “introduced the practice of the worship at Constantinople.”[29]

Modern scholarship has gone back and forth as to how much of the original Indo-Persian Mitra-Mithra cultus affected Roman Mithraism, which demonstrates a distinct development but which nonetheless follows a pattern of this earlier solar mythos and ritual.

The theory of continuity from the Iranian to Roman Mithraism, developed famously by Dr. Franz Cumont in the 20th century, has been largely rejected by many scholars. Yet, Plutarch himself, in Life of Pompey, related that followers of Mithras “continue to the present time” the secret rites of the Cilician pirates, “having been first instituted by them.” So too does the ancient writer Porphyry (234-ca 305 AD) state that the Roman Mithraists themselves believed their religion had been founded by the Persian savior Zoroaster.

Statue of Tiridates I of Armenia; André, 1687; Parc et jardins du château de Versailles (Photo: Eupator).

In discussing what may have been recounted by ancient writers, asserted to have written many volumes about Mithraism, such as Eubulus of Palestine and a certain Pallas, Gordon remarks: “Certainly Zoroaster would have figured largely; and so would the Persians and the magi.”[8,21,23]

It seems that the ancients did not divorce themselves from the eastern roots of Mithraism, as exemplified also by the remarks of Dio Cassius, who related that in 66 AD the king of Armenia, Tiridates, visited Rome. Cassius states that the dignitary worshiped Mithra; yet, he does not indicate any distinction between Armenia’s religion and Roman Mithraism.

It is apparent from the testimonies of ancient sources that they perceived Mithraism as having a Persian origin; hence, it would seem that any true picture of the development of Roman Mithraism must include the latter’s relationship to the earlier Persian cultus, as well as its Asia Minor and Armenian offshoots. Current scholarship is summarized thus by Dr. Beck: “Since the 1970s, scholars of western Mithraism have generally agreed that Cumont’s master narrative of east-west transfer is unsustainable; but… recent trends in the scholarship on Iranian religion, by modifying the picture of that religion prior to the birth of the western mysteries, now render a revised Cumontian scenario of east-west transfer and continuities once again viable.”[12]

In a massive anthology titled, Armenian and Iranian Studies, Dr. James R. Russell essentially proves that Roman Mithraism had its origins in, not only Persian or Iranian Mithraism and Zoroastrianism, but also in Armenian religion centuries before the common era.[36]

The many faces of Mithra

Mainstream scholarship speaks of at least three Mithras:

- Mitra, the Vedic god

- Mithra, the Persian deity

- Mithras, the Greco-Roman mysteries

The Persian Mithra apparently developed differently in various places, such as in Armenia, where there appeared to be an emphasis on characteristics not overtly present in Roman Mithraism but later found as motifs in Christianity, including the virgin-mother goddess. This Armenian Mithraism is evidently a continuity of the Mithraism of Asia Minor and the Near East. The development of gods into different forms, shapes, colors, ethnicities and other attributes according to location, era and so on, is not only quite common but also the norm. Thus, we have hundreds of gods and goddesses who are in many ways interchangeable but who have adopted various differences based on geographical and environmental factors.

Over the centuries — in fact, from the earliest Christian times — Mithraism has been compared to Christianity, revealing numerous similarities between the two faiths’ doctrines and traditions, including the stories of their respective god men. In developing this analysis, it should be kept in mind that elements from Roman, Armenian and Persian Mithraism are adopted, not as a whole ideology but as separate items that may have affected the creation of Christianity, whether directly through the mechanism of Mithraism or through another Pagan source within the Roman Empire and beyond. The evidence points to these motifs and elements being incorporated into Christianity, not as a whole from one source, but from many sources including Mithraism. The following list represents, not a solidified myth or narrative about one particular Mithra or form of the god as developed in one particular culture and era but, rather, a combination of them all for ease of reference as to any possible influences upon Christianity under the name of Mitra | Mithra | Mithras.

Mithra has the following in common with Jesus

- Mithra was born on December 25 of the virgin Anahita.

- The babe was wrapped in swaddling clothes, placed in a manger and attended by shepherds.

- Mithra was considered to be a great traveling teacher and master.

- He had 12 companions or disciples.

- He performed miracles.

- As the “great bull of the sun,” Mithra sacrificed himself for world peace.

- He ascended to heaven.

- Mithra was viewed as the good shepherd, the way, the truth and the light; the redeemer, the savior, and the messiah.

- Mithra is omniscient, as he “hears all, sees all, knows all: none can deceive him.”

- He was identified with both the lion and the lamb.

- His sacred day was Sunday, the Lord’s day, hundreds of years before the appearance of Christ.

- His religion had a eucharist or Lord’s supper.

- Mithra set his marks on the foreheads of his soldiers.

- Mithraism emphasized baptism.

December 25 birthday

The similarities between Mithraism and Christianity have included their chapels, celibacy and the term “father” for priest and, it is notoriously claimed, the December 25 birth date. Over the centuries, apologists who contend that Mithraism copied Christianity have nevertheless asserted that the December 25 birth date was taken from Mithraism. As Sir Arthur Weigall writes: “December 25 was really the date of, not of the birth of Jesus, but of the sun-god Mithra. Horus, son of Isis, however, was in very early times identified with Ra, the Egyptian sun-god, and hence with Mithra….”[40] Mithra’s birthday on December 25 has been so widely claimed that the Catholic Encyclopedia (“Mithraism”) remarks: “The 25 December was observed as his birthday, the natalis invicti, the rebirth of the winter-sun, unconquered by the rigors of the season.”

Yet this contention of Mithra’s birthday being on December 25 or the winter solstice is disputed because there is no hard archaeological or literary evidence of the Roman Mithras specifically being named as having been born at that time. Dr. Alvar writes: “There is no evidence of any kind, not even a hint, from within the cult that this, or any other winter day, was important in the Mithraic calendar.”[8]

In analyzing the evidence, we must keep in mind all the destruction that has taken place over the past 2,000 years — including that of many Mithraic remains and texts — as well as the fact that several of these germane parallels constituted mysteries that may or may not have been recorded in the first place, or the meanings of which have been obscured.

The claim about the Roman Mithras’ birth on Christmas is evidently based on the Calendar of Filocalus or Philocalian Calendar (ca 354 AD), which mentions that December 25 represents the “Birthday of the Unconquered,” understood to mean the sun and Mithras being Sol Invictus. Whether this represents Mithras’ birthday specifically or merely that of Emperor Aurelian’s Sol Invictus, with whom Mithras had become identified, the Calendar also lists the day — the winter solstice birth of the sun — as that of natus Christus in Betleem Iudeae | Birth of Christ in Bethlehem Judea. Moreover, it would seem that there is more to this story, as Aurelian was the first to institute officially the winter solstice as the birthday of Sol Invictus (Dies Natalis Solis Invicti) in 274 AD.[24] It is contended that Aurelian’s move was in response to Mithras’ popularity.[33] One would thus wonder why the emperor would be so motivated if Mithras had nothing whatever to do with the sun god’s traditional birthday: a disconnect that would be unusual for any solar deity.

The claim about the Roman Mithras’ birth on Christmas is evidently based on the Calendar of Filocalus or Philocalian Calendar (ca 354 AD), which mentions that December 25 represents the “Birthday of the Unconquered,” understood to mean the sun and Mithras being Sol Invictus. Whether this represents Mithras’ birthday specifically or merely that of Emperor Aurelian’s Sol Invictus, with whom Mithras had become identified, the Calendar also lists the day — the winter solstice birth of the sun — as that of natus Christus in Betleem Iudeae | Birth of Christ in Bethlehem Judea. Moreover, it would seem that there is more to this story, as Aurelian was the first to institute officially the winter solstice as the birthday of Sol Invictus (Dies Natalis Solis Invicti) in 274 AD.[24] It is contended that Aurelian’s move was in response to Mithras’ popularity.[33] One would thus wonder why the emperor would be so motivated if Mithras had nothing whatever to do with the sun god’s traditional birthday: a disconnect that would be unusual for any solar deity.

Regardless of whether or not the artifacts of the Roman Mithras’ votaries reflect the attribution of the sun god’s birthday to him specifically, many in the empire did identify the mysteries icon and Sol Invictus as being one, evidenced by the inscriptions of “Sol Invictus Mithras” and the many images of Mithras and the sun together, representing two sides of the same coin or each other’s alter ego. Hence, the placement of Mithras’ birth on this feast day of the sun is understandable and, despite the lack of concrete evidence, this date, quite plausibly, was recognized in this manner in antiquity in the Roman Empire.

Persian winter festivals

It is clear that the ancient peoples, from whom Mithraism sprang long before it became Romanized, were very much involved in winter festivals so common globally among many other cultures. In this regard, discussing the Iranian month of Asiyadaya, which corresponds to November/December, Mithraic scholar Dr. Mary Boyce remarks: “… it is at this time of year that the Zoroastrian festival of Sada takes place, which is not only probably pre-Zoroastrian in origin, but may even go back to proto-Indo-European times. For Sada is a great open-air festival, of a kind celebrated widely among the Indo-European peoples, with the intention of strengthening the heavenly fire, the sun, in its winter decline and feebleness. Sun and fire being of profound significance in the Old Iranian religion, this is a festival which one would expect the Medes and Persians to have brought with them into their new lands… Sada is not, however, a feast in honor of the god of Fire, Atar, but is rather for the general strengthening of the creation of fire against the onslaught of winter.” This ancient Persian winter festival therefore celebrates the strengthening of the fire, or sun, in the face of its winter decline, just as virtually every winter-solstice festivity is intended to do.

Yet, as Dr. Boyce says, this “Zoroastrian” winter celebration is likely to be pre-Zoroastrian and even proto-Indo-European, which means that it dates back far into the hoary mists of time, possibly tens of thousands of years ago. And one would indeed expect the Medes and Persians to have brought this festival with them into their new lands, including the Near East, where they would have eventually encountered Romans, who could hardly have missed this common solar motif celebrated worldwide in numerous ways.

The same may be said as concerns another Persian or Zoroastrian winter celebration called Yalda, which is the festival of the longest night of the year, taking place on December 20, or the day before the winter solstice: “Yalda has a history as long as the Mithraism religion. The Mithraists believed that this night is the night of the birth of Mithra, Persian god of light and truth. At the morning of the longest night of the year the Mithra is born from a virgin mother…. In Zoroastrian tradition, the winter solstice with the longest night of the year was an auspicious day, and included customs intended to protect people from misfortune…. The Eve of the Yalda has great significance in the Iranian calendar. It is the eve of the birth of Mithra, the Sun God, who symbolized light, goodness and strength on earth. Shab-e Yalda is a time of joy. Yalda is a Syriac word meaning birth. Mithra worshippers used the term ‘yalda’ specifically with reference to the birth of Mithra. As the longest night of the year, the Eve of Yalda (Shab-e Yalda) is also a turning point, after which the days grow longer. In ancient times it symbolized the triumph of the sun god over the powers of darkness.”[7] It is likely that this festival does indeed derive from remote antiquity, and it is evident that the ancient Persians were well aware of the winter solstice and its meaning as found in numerous other cultures: to wit, the annual rebirth, renewal or resurrection of the sun. In the end the effect is the same: Christmas is the birthday, not of the son of God, but of the sun.

Indeed, there is much evidence, including many ancient monumental alignments, to demonstrate that this highly noticeable and cherished winter-solstice celebration began hundreds to thousands of years before the common era in numerous parts of the world. The observation was thus provably taken over by Christianity, not as biblical doctrine but as a later tradition meant to compete with the Pagan cults, a move we contend occurred with numerous other supposedly Christian motifs, including many that are in the New Testament.

Rock-born Mithra

Mithra’s genesis out of a rock, analogous to the birth in caves of a number of gods, including Jesus in the apocryphal non-canonical texts, was followed by his adoration by shepherds, another motif that found its way into Christianity. Regarding the birth in caves, likewise common to pre-Christian gods and present in the early legends of Jesus, Weigall relates: “…the cave shown at Bethlehem as the birthplace of Jesus was actually a rock shrine in which the god Tammuz or Adonis was worshiped, as the early Christian father Jerome tells us; and its adoption as the scene of the birth of our Lord was one of those frequent instances of the taking over by Christians of a pagan sacred site. The propriety of this appropriation was increased by the fact that the worship of a god in a cave was commonplace in paganism: Apollo, Cybele, Demeter, Herakles, Hermes, Mithra and Poseidon were all adored in caves; Hermes, the Greek Logos, being actually born of Maia in a cave, and Mithra being ‘rock-born.'”[40]

As the rock-born, Mithras was called Theos ek Petras, or the God from the Rock. As Weigall also relates: “Indeed, it may be that the reason of the Vatican hill at Rome being regarded as sacred to Peter, the Christian ‘Rock,’ was that it was already sacred to Mithra, for Mithraic remains have been found there.”[40] Mithras was The Rock, or Peter, and was also double-faced, like Janus the key holder, likewise a prototype for the apostle Peter. Hence, when Jesus is made to say, in the apparent interpolation at Matthew 16:12, that the keys of the kingdom of heaven are given to Peter and that the church is to be built upon Peter as a representative of Rome, he is usurping the authority of Mithraism, which was precisely headquartered on what became Vatican Hill. “Mithraic remains on Vatican Hill are found underneath the later Christian edifices, which proves the Mithra cult was there first.”

By the time the Christian hierarchy prevailed in Rome, Mithra had already been a popular cult, with popes, bishops, etc., and its doctrines were well established and widespread, reflecting a certain antiquity. Mithraic ruins are abundant throughout the Roman Empire, beginning in the late first century AD. By contrast, “the earliest church remains, found in Dura-Europos, date only from around 230 AD.”

Virgin mother Anahita

Unlike various other rock- or cave-born gods, Mithra is not depicted in the Roman cultus as being born of a mortal woman or a goddess; hence, it is claimed that he was not born of a virgin. However, a number of writers over the centuries have asserted otherwise, including several modern Persian and Armenian scholars who are apparently reflecting an ancient tradition from Near-Eastern Mithraism. “The worship of Mithra and Anahita, the virgin mother of Mithra, was well-known in the Achaemenian period.”

Sassanid king Khosrow flanked by Anahita and Ahura Mazda; 7th century AD, Taq-e Bostan, Iran (Photo: Phillipe Chavin).

For example, Dr. Badi Badiozamani says that a person named Mehr or Mithra was “born of a virgin named Nahid Anahita (‘immaculate’)” and that “the worship of Mithra and Anahita, the virgin mother of Mithra, was well-known in the Achaemenian period (558-330 BC)…”[11] Dr. Mohammed Ali Amir-Moezzi states: “In Mithraism, as in popular Mazdaism, Anahid, Mithra’s mother is a virgin.”[9] Comparing the rock birth with that of the virgin mother, Dr. Amir-Moezzi also says: “…there is therefore an analogy between the rock, a symbol of incorruptibility, giving birth to the Iranian god and that (same) one’s mother, Anahid, eternally virgin and young.”[9]

In Mithraic Iconography and Ideology, Dr. Leroy A. Campbell calls Anahita the “great goddess of virgin purity,”[17] and religious-history professor Dr. Claas J. Bleeker says, “In the Avestan religion she is the typical virgin.”[14] One modern writer portrays the Mithra myth thus: “According to Persian mythology, Mithras was born of a virgin given the title ‘Mother of God.'”[4]

The Parthian princes of Armenia were all priests of Mithras, and an entire district of this land was dedicated to the virgin mother Anahita. Many Mithraeums, or Mithraic temples, were built in Armenia, which remained one of the last strongholds of Mithraism. The largest near-eastern Mithraeum was built in western Persia at Kangavar, dedicated to “Anahita, the Immaculate Virgin Mother of the Lord Mithras.”

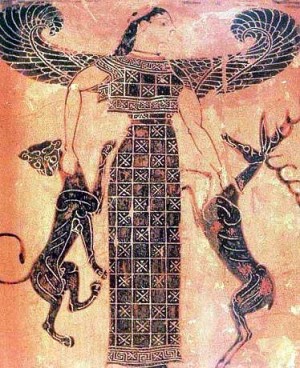

Anahita, also known as “Anaitis”— whose very name means pure and untainted — and who was equated in antiquity with the virgin goddess Artemis — is certainly an Indo-Iranian goddess of some antiquity, dating back at least to the first half of the first millennium prior to the common era and enjoying widespread popularity around Asia Minor. Indeed, Anahita has been called “the best known divinity of the Persians” in Asia Minor.[18]

Concerning Mithra, Schaff-Herzog says: “The Achaemenidae worshiped him as making the great triad with Ahura and Anahita.”[29] Ostensibly, this triad was the same as God the Father, the Virgin and Jesus, which would tend to confirm the assertion that Anahita was Mithra’s virgin mother. That Anahita was closely associated with Mithra at least five centuries before the common era is evident from the equation made by Herodotus (1.131) in naming Mitra as the Persian counterpart of the Near- and Middle-Eastern goddesses Alilat and Mylitta.[18]

Mithra’s prototype, the Indian Mitra, was likewise born of Aditi, mother of the gods, the inviolable or virgin dawn. Hence, we would expect an earlier form of Mithra also to possess this virgin-mother motif, which seems to have been lost or deliberately severed in the all-male Roman Mithraism.

The pre-Christian divine birth and virgin-mother motifs are well known to scholars and documented in the archaeological and literary records, as verified by Dr. Marguerite Rigoglioso in The Cult of the Divine Birth in Ancient Greece and Virgin Mother Goddesses of Antiquity. For more information, read: Mithra Born of a Virgin Mother and Mithra and the Twelve.

The teaching god and the twelve disciples

Mithra surrounded by the Twelve anthropomorphized signs of the Zodiac, Mithraeum of San Clemente, 3rd century AD.

The theme of the teaching god and the 12 is found within Mithraism. Mithra is depicted as being surrounded by the 12 zodiac signs on a number of monuments and in the writings of Porphyry (4.16), for one. These 12 signs are sometimes portrayed as humans and, as they have been in the case of numerous sun gods, could be called Mithra’s 12 companions or disciples.

Regarding the 12, John M. Robertson says: “On Mithraic monuments we find representations of twelve episodes, probably corresponding to the twelve labors in the stories of Heracles, Samson and other Sun-heroes, and probably also connected with initiation.”[35] The comparison of this common motif with Jesus and the 12 has been made on many occasions, including in an extensive chapter by Professor A. Deman in Mithraic Studies titled, “Mithras and Christ: some iconographical similarities.”

Early church fathers on Mithraism

Mithraism was so popular in the Roman Empire and so similar in important aspects to Christianity that several church fathers were compelled to address it, disparagingly of course. These fathers included Justin Martyr, Tertullian, Julius Firmicus Maternus and Augustine, all of whom attributed these striking correspondences to the prescient devil. In other words, the devil anticipated Christ and set about to fool the Pagans by imitating the coming messiah. In reality, the testimony of these church fathers confirms that these various motifs, characteristics, traditions and myths predate Christianity. Concerning this devil-did-it argument, in The Worship of Nature Sir James G. Frazer remarks: “If the Mithraic mysteries were indeed a Satanic copy of a divine original, we are driven to conclude that Christianity took a leaf out of the devil’s book when it fixed the birth of the Savior on the twenty-fifth of December; for there can be no doubt that the day in question was celebrated as the birthday of the Sun by the heathen before the Church, by an afterthought, arbitrarily transferred the Nativity of its Founder from the sixth of January to the twenty-fifth of December.”

Regarding the various similarities between Mithra and Christ, as well as the defenses of the church fathers, the author of The Existence of Christ Disproved remarks: “Justin Martyr, Church Father Augustine, Firmicus, Justin, Tertullian, and others, having perceived the exact resemblance between the religion of Christ and the religion of Mithra, did, with an impertinence only to be equaled by its outrageous absurdity, insist that the devil, jealous and malignant, induced the Persians to establish a religion the exact image of Christianity that was to be — for these worthy saints and sinners of the church could not deny that the worship of Mithra preceded that of Christ — so that, to get out of the ditch, they summoned the devil to their aid, and with the most astonishing assurance, thus accounted for the striking similarity between the Persian and the Christian religion, the worship of Mithra and the worship of Christ; a mode of getting rid of a difficulty that is at once so stupid and absurd, that it would be almost equally stupid and absurd seriously to refute it.”

In response to a question about Tertullian’s discussion of a purported Mithraic forehead mark, Dr. Richard Gordon says: “In general, in studying Mithras, and the other Greco-oriental mystery cults, it is good practice to steer clear of all information provided by Christian writers: they are not ‘sources,’ they are violent apologists, and one does best not to believe a word they say, however tempting it is to supplement our ignorance with such stuff.” He also cautions about speculation concerning Mithraism and states that “there is practically no limit to the fantasies of scholars….”: an interesting admission about the hallowed halls of academia.[8,21,23]

Priority: Mithraism or Christianity?

It is obvious from the remarks of the church fathers and from the literary and archaeological record that Mithraism in some form preceded Christianity by centuries. The fact is: there is no Christian archaeological evidence earlier than the earliest Roman Mithraic archaeological evidence, and the preponderance of evidence points to Christianity being formulated during the second century, not based on a historical personage of the early first century. One important example, the canonical gospels, as we have them, do not show up clearly in the literary record until the end of the second century.

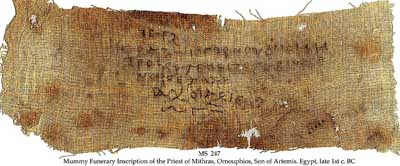

Mithra’s pre-Christian roots are attested in the Vedic and Avestan texts, as well as by historians such as Herodotus [1.131] and Xenophon [Cyrop. viii. 5, 53 and c. iv. 24], among others. Nor is it likely that the Roman Mithras would not essentially be the same as the Indian sun god Mitra and the Persian, Armenian and Phrygian Mithra in his major attributes, as well as some of his most pertinent rites. Moreover, it is erroneously asserted that because Mithraism was a mystery cult, it did not leave any written record. In reality, much evidence of Mithra worship has been destroyed, including not only monuments, iconography and other artifacts, but also numerous books by ancient authors. The existence of written evidence is indicated, for example, by an Egyptian cloth manuscript from the first century BC called, “Mummy Funerary Inscription of the Priest of Mithras, Ornouphios, Son of Artemis” or MS 247.

As previously noted, two of the ancient writers on Mithraism are Pallas, and Eubulus, the latter of whom, according to Jerome (Against Jovinianus; Schaff), “wrote the history of Mithras in many volumes.” In discussions of Eubulus and Pallas, Porphyry too related that there were “several elaborate treatises setting forth the religion of Mithra.” The writings of the early Church fathers themselves provide much evidence as to what Mithraism was all about, as do the archaeological artifacts stretching from India to Scotland.

These many written volumes on Mithraism doubtlessly contained much interesting information that was damaging to Christianity, such as the important correspondences between the lives of Mithra and Jesus, as well as identical symbols such as the cross, and rites such as baptism and the eucharist. Indeed, Mithraism was so similar to Christianity that it gave fits to the early church fathers, as it does today to apologists, who attempt both to deny the similarities and yet to claim that these (non-existent) correspondences were plagiarized by Mithraism from Christianity.

For centuries prior to the Christian era, the god Mithra was revered, and germane elements of Mithraism are known to have preceded Christianity by hundreds to thousands of years. Regardless of attempts to make Mithraism the plagiarist of Christianity, the fact remains that Mithraism was first and well established in the West, as least decades before Christianity had any significant influence.

References

- 1. “Chronography of 354,” en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Calendar_of_Filocalus

- 2. “Mithraic Mysteries,” en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mithraic_mysteries

- 3. “Mithraism,” www.catholic.org/encyclopedia/view.php?id=8042

- 4. “Mithraism and Christianity,” meta-religion.com/World_Religions/Ancient_religions/Mesopotamia/Mithraism/ mithraism_and_christianity_i.htm

- 5. “Mithras in Comparison With Other Belief Systems,” en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mithras_in_Comparison_With_Other_Belief_Systems

- 6. “Mitra,” en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mitra

- 7. “Yalda,” en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yalda

- 8. Alvar, Jaime, and R.L. Gordon. Romanising Oriental Gods: Myth, Salvation and Ethics in the Cults of Cybele, Isis and Mithras. Leiden/Boston: Brill, 2008.

- 9. Amir-Moezzi, Mohammed Ali. La religion discrète: croyances et pratiques spirituelles dans l’islam shi’ite. Paris: Libr. Philosophique Vrin, 2006.

- 10. Anonymous. The Existence of Christ Disproved. Private Printing by “A German Jew,” 1840.

- 11. Badiozamani, Badi. Iran and America: Rekindling a Lost Love. California: East-West Understanding Press, 2005.

- 12. Beck, Roger. Beck on Mithraism. England/Vermont: Ashgate Pub., 2004.

- 13. Berry, Gerald. Religions of the World. New York: Barnes & Noble, 1955.

- 14. Bleeker, Claas J. The Sacred Bridge: Researches into the Nature and Structure of Religion. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1963.

- 15. Boyce, Mary. “Mithraism: Mithra Khsathrapati and his brother Ahura.” www.iranchamber.com/religions/articles/mithra_khsathrapati_ahura.php

- 16. A History of Zoroastrianism, II. Leiden/Köln: E.J. Brill, 1982.

- 17. Campbell, LeRoy A. Mithraic Iconography and Ideology. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1968.

- 18. de Jong, Albert. Traditions of the Magi: Zoroastrianism in Greek and Latin Literature. Leiden/New York: Brill, 1997.

- 19. Forbes, Bruce David. Christmas: A Candid History. Berkeley/London: University of California Press, 2007.

- 20. Frazer, James G. The Worship of Nature, I. London: Macmillan, 1926.

- 21. Gordon, Richard L. “FAQ.” Electronic Journal of Mithraic Studies, www.hums.canterbury.ac.nz/clas/ejms/faq.htm

- 22. “The date and significance of CIMRM 593 (British Museum, Townley Collection).”

- 23. Journal of Mithraic Studies, II (148-174). hums.canterbury.ac.nz/clas/ejms/out_of_print/JMSv2n2/ JMSv2n2Gordon.pdf

- 24. Halsberghe, Gaston H. The Cult of Sol Invictus. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1972.

- 25. Hinnells, John R., ed. Mithraic Studies: Proceedings of the First International Congress of Mithraic Studies. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1975.

- 26. Kosso, Cynthia, and Anne Scott. The Nature and Function of Water, Baths, Bathing and Hygiene from Antiquity through the Renaissance. Leiden/Boston: Brill, 2009.

- 27. Lundy, John P. Monumental Christianity. New York: J.W. Bouton, 1876.

- 28. Molnar, Michael R. The Star of Bethlehem: The Legacy of the Magi. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1999.

- 29. The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia, VII. eds. Samuel M. Jackson and George William Gilmore. New York/London: Funk and Wagnalls Company, 1910.

- 30. Plutarch. “Life of Pompey.” The Parallel Lives by Plutarch, V. Loeb, 1917; penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Plutarch/Lives/ Pompey*.html#24

- 31. Porphyry. Selects Works of Porphyry. London: T. Rodd, 1823.

- 32. Prajnanananda, Swami. Christ the Saviour and Christ Myth. Calcutta: Ramakrishna Vedanta Math, 1984.

- 33. Restaud, Penne L. Christmas in America: A History. New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1995.

- 34. Robert, Alexander, and James Donaldson, eds. Ante-Nicene Christian Library, XVIII: The Clementine Homilies. Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1870.

- 35. Robertson, John M. Pagan Christs. Dorset, 1966.

- 36. Russell, James R. Armenian and Iranian Studies. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2004.

- 37. Schaff, Philip, and Henry Wace. A Select Library of Nicene and Post-Nicene Father of the Christian Church, VI. New York: The Christian Literature Company, 1893.

- 38. Schironi, Francesca, and Arthus S. Hunt. From Alexandria to Babylon: Near Eastern Languages and Hellenistic Erudition in the Oxyrhynchus Glossary. Berlin/New York: Walter de Gruyter, 2009.

- 39. Srinivasan, Doris. On the Cusp of an Era: Art in the Pre-Kusana World. Leiden/Boston: Brill, 2007.

- 40. Weigall, Arthur. The Paganism in Our Christianity. London: Thames & Hudson, 1923.

- 41. For more information and citations, see The Christ Conspiracy and The Christ Myth Anthology.

Source: Truth Be Known | Edited by Dady Chery for Haiti Chery

Comments

Mithra: The Pagan Christ — No Comments