Choucoune Story and Song, With English Translation of Lyrics By Dady Chery

English translation of lyrics by Dady Chery for Haiti Chery

Creole lyrics, by Oswald Durand, courtesy of Gage Averill

Music by Michel Mauleart Monton, performed by Martha Jean-Claude

History by Louis J. Auguste, MD

Haiti Chery

By Oswald Durand

Translated from the Creole by Dady Chéry.

1. Behind a thick cactus grove

Yesterday I met my Choucoune

Oh! That smile when she saw me

I said “Heaven, such beauty!” (2X)

She said, “Dear, do you think so?”

(Chorus:) Little birds, who listened deep in these woods (2X)

When I think of this

It brings me such pain

Ever since that day

Both my feet in chains

When I think of this

It brings me such pain

Both my feet in chains

2. Choucoune is a marabou,

Eyes as bright as candlelight

Her breasts ever so bouncy

Ah! If Choucoune had been true! (2X)

We stayed and talked a long while

(Chorus:) Little birds looked so happy in these woods (2X)

Better forget this

The pain is too great

Ever since that day

Both my feet in chains

Better forget this

The pain is too great

Both my feet in chains

3. Choucoune’s teeth are white as milk

Her lips pink as kayimit

She’s not fat but well padded

Women like this send me fast (2X)

Though yesterday’s not today

(Chorus:) Little birds, who heard every word she said (2X)

If you think of this

It will make you sad

Ever since that day

Both my feet in chains

If you think of this

It will make you sad

Both my feet in chains

4. We went to her mother’s house

A straight-talking old woman

Soon as she saw me she said

Ah! This one is my favorite! (2X)

We drank up her hot cocoa

(Chorus:) Is all lost, dear little birds of these woods (2X)

Better forget this!

The pain is too great

Ever since that day

Both my feet in chains

Better forget this

The pain is too great

Both my feet in chains

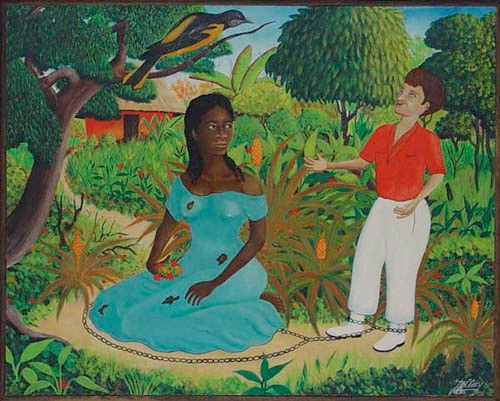

5. Young white fellow came around

Trim red beard on his pink face

Pocket watch and hair of silk

My troubles, he brought them all

My troubles, he brought them when

He found my pretty Choucoune

(Chorus:) Sang French words that made my Choucoune love him (2X)

Better forget this

The pain is too great

Choucoune left me here

Both my feet in chains

Better forget this

The pain is too great

Both my feet in chains

Notes on the translation. This is the first complete English translation of Oswald Durand’s marvelous poem. I strived to keep the meaning and meter; the rhyme will have to wait for a better poet. The lines “A si choukoun té fidel, Nou rété kozé lontan” are sometimes replaced with “A si choukoun té fidel, Mwen ta renmen li lontan” (Ah! If Choucoune had been true, I’d have loved her a long time,” which would seem more sensible. On the other hand, the heart of the poem is that the writer remembers his time with Choucoune, sometimes as if it happened yesterday, and other times as if it is happening now. He casually glides from past to present and back in his lamentations to his witnesses, the little birds. I respected the original lyrics found by Averill. Another small example of Durand’s genius that defies translation: “Pyé mwen nan chenn” is a Haitian Kreyòl proverb about being hopeless stuck on someone, and “Dé pyé mwen nan chenn” means doubly so. DC

Original Creole Lyrics, As Written By Oswald Durand

Courtesy of Gage Averill

1. Dèyè yon gwo touf pengwen

Lot jou mwen kontré Choukoun

Li souri lè li wè mwen

Mwen di : « Syèl a la bèl moun »

Mwen di : « Syèl a la bèl moun »

Li di : « Ou trouve sa chè ? »

(Chorus:) Ti zwazo nan bwa ki t’ apé kouté (x2)

Kon mwen sonjé sa

Mwen genyen lapen

Ka dépi jou-sa

De pyé mwen nan chen

Kon mwen sonjé sa

Mwen genyen lapen

De pyé mwen nan chen

2. Choukoun sé yon marabou

Jé li klére kon chandèl

Li genyen tété debou

A si choukoun té fidèl

A si choukoun té fidèl

Nou rété kozé lontan

(Chorus:) Jis zwazo nan bwa té parèt kontan (x2)

Pito bliyé sa

Sé two gran lapen

Ka dépi jou-sa

De pyé mwen nan chen

Pito bliyé sa

Sé two gran lapen

De pyé mwen nan chen

3. Ti dan Choukoun blan kou lèt

Bouch li koulè kayimit

Li pa gwo fanm, li gwosèt

Fanm konsa plè mwen touswit

Fanm konsa plè mwen touswit

Tan pasé pa tan jodi

(Chorus:) Zwezo te tandé tout sa li té di (x2)

Si ou sonjé sa

Yo dwé nan lapen

Ka dépi jou-sa

Dé pyé mwen nan chen

Si ou sonjé sa

Yo dwé nan lapen

Dé pyé mwen nan chen

4. N’alé lakay manman li

Yon granmoun ki byen onèt

Sito li wè mwen li di:

“A mwen kontan sila-a nèt”

“A mwen kontan sila-a nèt”

Nou bwe chokola nwa

(Chorus:) Eske tout sa fini, ti zwazo nan bwa (x2)

Pito bliyé sa

Sé two gran lapen

Ka dépi jou-sa

De pyé mwen nan chen

Pito bliyé sa

Sé two gran lapen

De pyé mwen nan chen

5. Yon ti blan vini rivé

Ti bab wouj, bèl figi woz

Mont sou koté, bel chivé

Malè mwen, li ki lakoz

Malè mwen, li ki lakoz

Li trouvé choukoun joli

(Chorus:) Li palé fransé, Choukoun renmen li (x2)

Pito bliyé sa

Sé two gran lapen

Choukoun kité mwen

Dé pyé mwen nan chen

Pito bliyé sa

Sé two gran lapen

Dé pyé mwen nan chen

The Story of Choucoune

By Louis J. Auguste, MD

Pikliz

For the past 500 years, Haiti has been part of the world’s history. As a member of the society of nations, Haiti and Haitians have made numerous worthy, but rarely heralded, contributions.

Need we mention the bravery of the future heroes of our Independence, who fought in Savannah under the banner of the French Army to help defeat the English Colonial forces and help free the United States of America?

Need we mention the foundation of the city of Chicago by Jean-Baptiste Point du Sable, a Haitian-born fur trader?

Need we mention the assistance provided to Simon Bolivar by Petion in the form of safe haven when his life was threatened, monetary support, tactical advice and even the provision of manpower to bolster his army?

Need we mention the generous contributions of all the Haitian teachers who responded to the call of our ancestors’ land in the days that followed the massive movement of African decolonization in the 1970s, when all these newly created nations were “dropped” by their former colonizers.

The list goes on and on. However, the greatest contribution of all is an intellectual one.

Haiti is one of the most vibrant and productive nations within the francophone community, when it comes to literary creation. Haitian writers, such as Dany Laferrière, are often called upon to represent Canada at the International Book Fairs in Paris. Novelists such as Jacques Roumain have been translated in more than 20 languages and read all over the world.

When it comes to music, the Haitian influence has also been enormous. Throughout the history of the new world, it is undeniable that Haitian rhythms and compositions have impacted both Latin and Caribbean music, particularly Cuban, Guadeloupean and Dominican, but this contribution has seldom been acknowledged.

The astute student of our music will remember that among others, Guy Durosier and Raoul Guillaume’s song, “Ma Brune,” has been translated into Spanish as “Morena” and interpreted by many South American artists. Certainly, it gives us a sense of pride to see how some of our musical creations are appreciated abroad.

It is painful, however, that one of our most celebrated meringues is hijacked, without giving credit to its original composer.

As a child growing up in Haiti, I remember being rocked to sleep by my mother to the beautiful tune of “Choucoune.”

This slow meringue, perhaps more than any other, has been interpreted by most Haitian choirs, orchestras, bands or ensembles. I never thought that any single Haitian would doubt that this song is ours, belongs to us and to none other.

However, this tune has become better known with the lyrics of “Yellow Bird” than those of “Choucoune.” If you ask a Jamaican, he will have no hesitation in answering that it is a Jamaican song.

Young Haitian-Americans surveyed recently were not sure whether it was a Jamaican song translated into Kreyòl or a Haitian song translated into English. Even the German-Haitian artist Cornelia Schutt, also known as Ti Corn, in her CD “Caribbean Ballads” (1991-Gema), sings “Yellow Bird” and lists it as “traditional.”

My frustration growing, I went on the internet to look for the name of the composer of “Choucoune.” Both AskJeeves.com and Google had no match for the question. I contacted numerous music stores in an attempt to procure a copy of the scores of the Choucoune. No luck. I went on e-Bay, hoping to be able to buy perhaps an old sheet music, with the scores of “Choucoune.” There again, no luck. I decided therefore to search “Yellow Bird.” On the first try on AskJeeves.com, there it was: Yellow Bird’s music was composed in the 1960s by Norman Luboff and the lyrics written by Alan and Marilyn Keith Bergman.

It had become clear to me that we were facing a case of stolen legacy, to use an expression rendered popular by James Richardson, who described how the glorious Egyptian tradition was falsely attributed to the Greeks by Eurocentric scholars. Did this happen because we Haitians fail to study our own history and to teach it to our children?

What is the true story of “Choucoune”?

Believe it or not, Choucoune was a real person. Her real name was Marie Noel Bélizaire. She was born in the Village of La-Plaine-du-Nord in 1853.

Ms. Bélizaire’s parents are not commonly known, but it is reported that she had two sisters. Unlike her sisters, Marie Noel was strikingly beautiful. She was given the nickname Choucoune. She was dark-skinned, but her hair was long and straight, defining the marabou type commonly used in the Haitian vernacular.

Before she could finish her elementary classes, she fell in love with a young man named Pierre Théodore. The two became involved in a common-law marriage. To support her family, she started a small business, detailing various articles of daily necessity. Soon however, Choucoune realized that the young man was unfaithful.

She left the village and moved to Cap Haïtien, the capital of the Northern Province of Haiti. She resided at 14, Rue Simon, in the Petite-Guinée neighborhood. She established a small restaurant near the Chapel of St-Joseph, located on Rue 19.

Her customers may have included one Oswald Durand, famous poet in those days in Cap Haïtien. He was 13 years older than Choucoune. Nevertheless a romantic relationship was quick to start between the two. They seemed to have enjoyed quite a few blissful moments. Those moments unfortunately were short, because Oswald Durand was a known womanizer and often described himself as “the gardener that waters all the flowers.” Choucoune looked for a more stable relationship and moved on.

Shortly thereafter, Oswald Durand was thrown in jail for having criticized some of the political leaders in Cap Haïtien. While sitting in his cell, a bird alit on his window, and Durand composed one of the most beautiful Haitian poems written in Kreyòl. Its title was Choucoune, and the year was 1883.

In it, the poet talks of Choucoune’s beauty, their happy moments, and the pain of their separation, when Choucoune preferred a young Frenchman over him. Choucoune never returned to Durand, despite the fact that he truly immortalized her. She kept looking for the perfect love that never came. In the latter part of her life she fell on hard times and returned to her native village.

She became insane and had to beg for her survival. My mother who, as a child, used to go to the celebration of Saint James in La-Plaine-du-Nord, told me that people would point to the fallen beauty and whisper:

“Here is Choucoune! Look at Choucoune!”

Choucoune died in 1924.

Durand’s poem was considered the best poem written inKreyòl, and 10 years later it attracted a young musician by the name of Michel Mauleart Monton.

Mauleart was born in New Orleans, Louisiana, of a Haitian father and an American mother. His father’s name was Milien Monton and he was a tailor. For unknown reasons, Michel was raised in Haiti by his older sister, Odila Monton, who owned a store on Rue du Magazin de l’État, in Port-au-Prince. He took music lessons from Mr. Toureau Lechaud and learned how to play the piano.

Under the spell of the rich tropical climate, the surreal and magical world of Haitian religion, and the classical European musical tradition, Mauleart combined these influences to compose numerous pieces that were celebrated in his days but that are not commonly known nowadays. They included: La Polka des Tailleurs (The Tailors’ Polka), L’amour et l’argent (Love and Money), P’tit Pierre (Little Peter), Les P’tits Suye Pye du Jeudi (The Thursday Dance Parties) and many others.

He is most famous, however, for putting to music Oswald Durand’s poem, Choucoune. The song was first performed in public in Port-au-Prince on May 14, 1893.

Choucoune was an instant success in Haiti and abroad. It was prominently featured during the festivities that marked the celebration of the Bicentennial of Port-au-Prince, in 1949.

Then Haiti was the main tourist attraction of the Caribbean. The noted visitors of the island included celebrities like Marian Anderson, Harry Belafonte, Elizabeth Taylor, and many others. Who first fell in love with the slow meringue of Choucoune? We will never know.

Let’s just say that in the 1950s, a composer named Norman Luboff heard the song and adapted the melody to new lyrics written by two songwriters, Alan and Marilyn Keith Bergman. The lyrics were also inspired by Durand’s poem, and Ti Zwazo (little bird in creole) became Yellow Bird. The song appeared on the Norman Luboff Choir’s Calypso Holiday LP album in 1957, described on the cover as a “serenade of a lonesome lover to an equally lonesome bird.”

The new version of the song gained quickly in popularity and became an easy-listening favorite across the United States. Artists recorded it on a dozen singles and, it was the main title on albums by the Mills Brothers, Roger Williams and Lawrence Welk. Today, the song is performed by every steel band, and it is a favorite request of tourists on cruises or vacationing in the Caribbean islands, who don’t know that it all started in 1883, in a Haitian jail.

Next time, you hear “Yellow Bird,” think of “Choucoune” and Oswald, and tell everyone proudly that they are singing a Haitian song.

For those of our readers who sing or play a musical instrument, we are happy to provide the score and the lyrics of “Choucoune,” with credit given to lyricist, composer, and arranger.

Sources: Haiti Chery (English translation of Creole lyrics; assembly of history, song, images, videos) | Louis J. Auguste (history) | Oswald Durand via Gage Averill (Creole lyrics) | You Tube Michel Mauleart Monton (music) Martha Jean-Claude (vocals)

Comments

Choucoune Story and Song, With English Translation of Lyrics By Dady Chery — No Comments